Intel’s heyday, Andy Grove, famously wrote in 1996 that “only the paranoid survive” in business. For two decades, the American semiconductor manufacturer seems not to have been sufficiently spurred on by fear.

The former American champion of Silicon Valley, which ruled the world of computing in a duo with Microsoft until the early 2000s, was unable to manage the shift to mobile Internet, then to artificial intelligence. Today, it is reduced to considering divestments, or even a dismantling.

The group is discussing several scenarios with its investment bankers Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs, Bloomberg reported. It could split into two entities, with chip design on one side and production on the other, which could be sold. It is also looking at which factory projects to abandon, to reduce costs. A merger and acquisition operation is not excluded. These options will be presented to the board of directors in September.

$20 billion in federal grants and loans

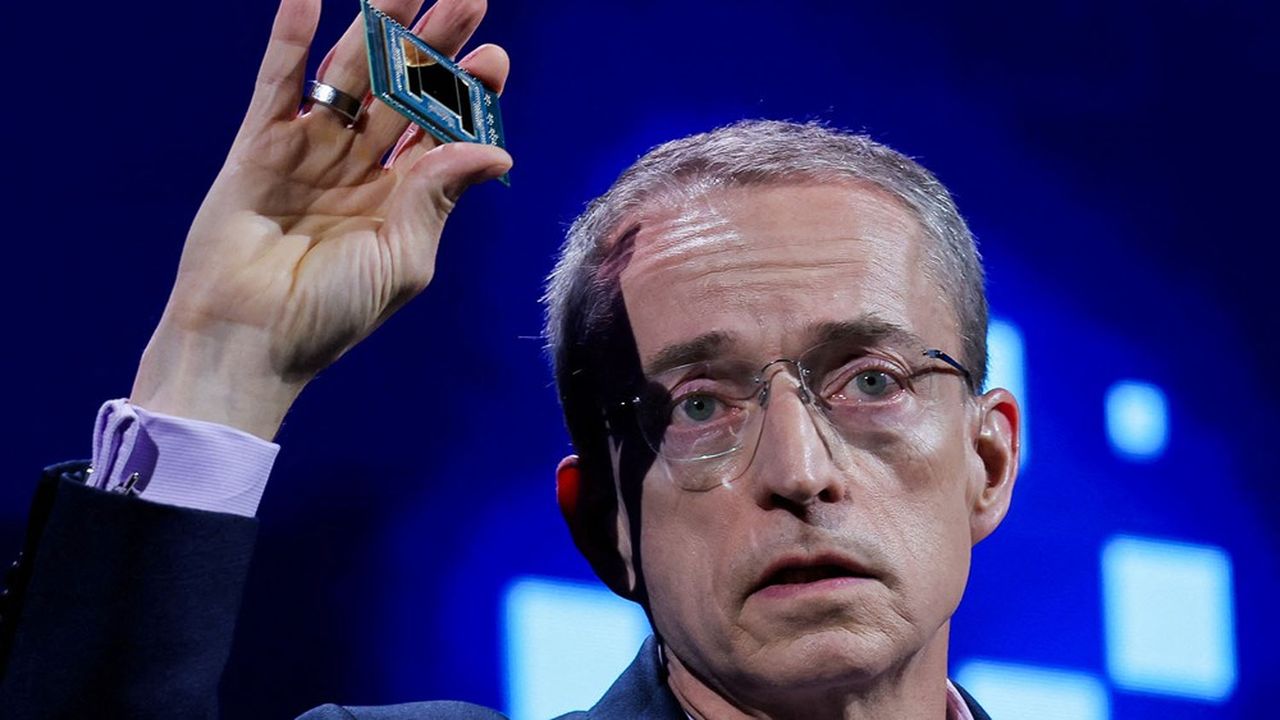

Intel has been in trouble for months. The red alert was sounded in early August, when CEO Pat Gelsinger announced the layoff of 15% of its workforce, or 16,000 employees worldwide, and the suspension of dividend payments until further notice. The same day, the company reported a quarterly loss of $1.6 billion and a slight decline in revenue.

Since the beginning of the year, the share price of the former semiconductor glory has plunged by 60%, before regaining 9.5% on Friday. The group is worth $94 billion on the stock market, a pittance compared to the $2.901 billion of the star of artificial intelligence chips Nvidia, which surpassed it in 2020. Intel was then worth around $200 billion.

Gelsinger has been trying to cut costs for some time now. In June, the company suspended the expansion of a microprocessor plant in Israel. It had also suspended industrial units in Ireland and Arizona. The company also postponed the start of work on the Magdeburg site in Germany, which is budgeted at 30 billion euros, pending significant European subsidies.

When it reported quarterly results in April, the group announced a 20% cut in capital expenditure for the current year, to around $26 billion, followed by a dip to $21.5 billion in 2025.

There is no shortage of subsidies, however. In the United States, the Biden administration has granted Intel the lion’s share of funding from the Chips Act, the law that aims to facilitate the relocation of chip production to the United States. Out of $39 billion in direct federal subsidies, the Santa Clara, California-based group is to receive $8.5 billion. This will be supplemented by $11.5 billion in loans. In comparison, the Taiwanese giant TSMC will “only” receive $6.6 billion in subsidies and $5 billion in loans.

A transitional economic model

But in reality, semiconductor manufacturers are facing a mountain of investment, and Intel, which has promised to spend $100 billion on its American factories alone, no longer has the financial means to match its ambitions. Having taken over in 2021, Pat Gelsinger found a way to stay in the global industrial race: he called on two investment funds, Brookfield Infrastructure Partners and Apollo Global Management, to co-invest in his factories. A first for Intel.

Furthermore, the leader bet on a new economic model distinguishing two businesses, design and production. On the one hand, Intel would continue to develop chips under its brand, having them manufactured either in-house or by other foundries, depending on needs.

On the other hand, it would manufacture chips for third parties, and these revenues would allow it to finance the opening of new factories, with the aim of rising to second place in the world behind TSMC in 2030.

Unfortunately, white-label revenues aren’t growing fast enough to offset weak revenue growth, which is itself linked to the fact that Intel has underinvested in artificial intelligence for too long. The American group will sell only $500 million of Gaudi AI chips this year, compared to $20 billion in revenue each quarter for Nvidia, points out “The Economist”.

In addition, Nvidia has developed an entire “AI” environment that Intel does not have, from processor networking equipment to the Cuda software platform, adds the British weekly. After Boeing’s industrial rout, Intel’s miseries are an additional blow to the glories of American capitalism.