As always when the Chinese Communist Party publishes a summary document of a political meeting, experts from the world’s second largest economy were able to engage in a detailed semantic analysis at the end of July. Faced with a system whose main geostrategic assets lie in its opacity, all that remains is to count the occurrences of this or that word to try to understand the changes in the doctrine and, implicitly, the power struggles that are being played out.

However, at the end of the third plenum of the Party, in the middle of summer, the conclusion is clear: the long-awaited reforms to pull the Chinese economy out of its languor have little chance of materializing. Certainly, as obligatory passages, the key words such as “reform”, “opening up” and “modernization” are there. Certainly, it is promised to work to create “a fairer and more dynamic market environment”. It is still necessary to recall that such a catalogue of pious wishes and empty formulas has been rehashed for years.

In an economy that urgently needs to be supported by household demand, the word “consumption” appears only 5 times, compared to 45 times for “technology”. In China, silences are as eloquent as words.

On the Asialyst website, sinologist Alex Payette asks the question: “We are entitled to wonder whether the emptiness of the documents and the palpable tension between certain sections are not the result of increasingly significant tensions at the top of the Party.” The expert lists several recent symptoms of the feverishness of a system “at the end of its rope”, including around the person of its number one, Xi Jinping.

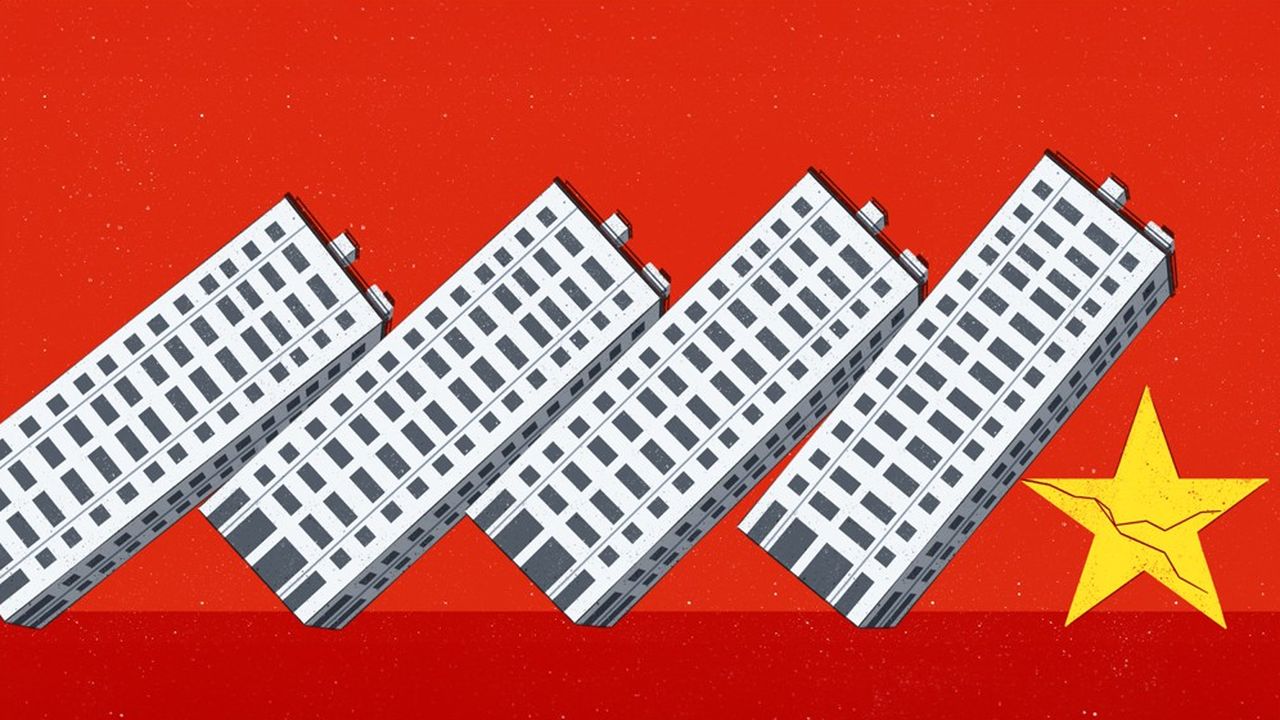

To explain such a tremor in the Chinese apparatus, we must recall the state of the economy, and the profound dysfunctions that are the cause. In the second quarter, Beijing saw its gross domestic product (GDP) grow by only 4.7%, compared to 5.3% in the first quarter. The real estate sector is failing to emerge from a crisis that began two years ago, despite the regime’s proactive measures.

Yet this sector alone accounts for a quarter of the national economy. More than two-thirds of household wealth is invested in property. In China, even more than elsewhere, when construction is not going well, nothing is going well. A form of wait-and-see attitude among economic agents is palpable, on the side of companies that are struggling to invest, and even more so among households, whose consumption is insufficient.

In a liberal political system, the solution would be to transfer purchasing power to households so that they can finally play their long-awaited role as economic drivers. The list of measures to be taken to move in this direction, particularly around strengthening social security, has been known to all economists for more than ten years. However, Beijing is only embarking on this path reluctantly.

Centrifugal forces

To understand this apparent inconsistency, we must remember the exclusively political nature of the Chinese Communist Party. If China, under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, developed its economy at top speed, it was in the service of strengthening the legitimacy of the Party, seriously undermined by the tragedies of Maoism. Four decades later, Xi Jinping demonstrates that the real obsession of the Chinese political system is that of its survival and its absolute control of the territory.

In a country that has drawn from its history the dread of centrifugal forces, Xi Jinping’s takeover, manifest on the political level, is being played out before our eyes on the economic level: there is no question of entrusting the future of China’s GDP to a force as volatile as household consumption. Because, as the current period demonstrates, even with the most gigantic propaganda machine in the world, household confidence cannot be decreed, nor their propensity to consume.

Weaning

The regime, partially weaned from its drug of overinvestment due to a deep real estate crisis, therefore has one final engine on which it hopes to act: exports. But here again, times have changed: at a time when Chinese manufacturers are collapsing under excess capacity, the confrontation with the United States and Europe is flagrant. Hence the extreme aggressiveness with which China is reacting to the measures announced by the European Union to protect itself from what it considers to be Chinese dumping – an aggressiveness that mainly denotes Beijing’s feverishness. Hence, above all, the 45 occurrences of the word “technology” in the recent Party document. It is by further establishing its lead in strategic industries (clean energy, batteries, artificial intelligence, etc.) that Beijing hopes to save its commercial omnipotence threatened by a latent rejection movement in the West.

It is therefore useless to hope that Beijing will take advantage of this return to school to finally rebalance its economy. And to believe that the balance of power with the West is destined to soften. Faced with its fragilities, the Chinese system most often falls back on its old reflexes: projecting power.