There was snow in Modena on February 18, 1898, when Enzo Ferrari was born. Alfredo the father, a small producer of railway materials (when it comes to twists of fate), only arrives at the registry office on the 20th and so he registers it. The car is still just an idea that seeks an outlet in reality, but the era is that in which the first engines appear destined to move the prototypes of the object of desire of which Enzo Ferrari will become a symbol in the world.

Little Ferrari, a schoolboy of little energy, fell in love with it at the age of ten when his father took him to watch one of the first races.

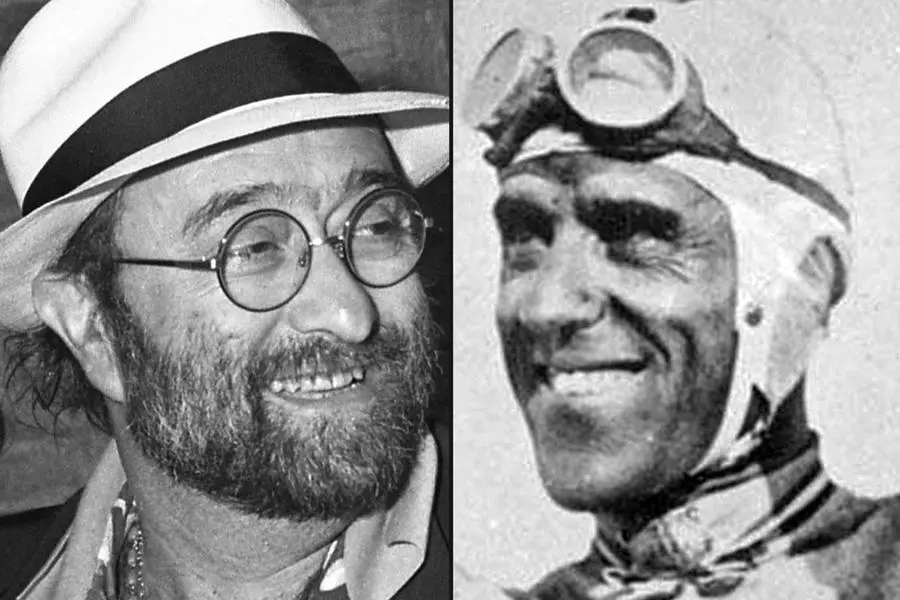

From there begins the visionary story of the patriarch of Maranello, whose white hair and, ever-present, dark glasses have transformed over time into the profile of an icon, recognizable everywhere, like Dante’s nose, Leonardo’s beard, like them an imperishable and planetary emblem of Italy: the other side of the prancing horse.

Even the little horse has a non-trivial history, Ferrari received it as a gift in 1923 on the Savio circuit from the counts Paola and Enrico Baracca, parents of Francesco Baracca, French air force pilot and hero of the First World War, who had painted it on the cockpit: it was his mother who encouraged him to keep it as a logo according to Ferrari himself: «It will bring her luck».

At that time, Ferrari was still a driver with good results, not excellent ones. Before that he had left school in the third technical institute, he had participated in the First World War, hard years in which he had lost his father and brother, resulting in a long hospitalization due to illness.

Having joined Cmn in Milan as a test driver, Ferrari made his debut as a driver on 5 October 1919 at Parma-Poggio in Berceto. A year later he was an official Alfa Romeo driver in the Targa Florio. His entrepreneurial soul led him to found the Scuderia Ferrari on 16 November 1929, which took part in world races with Alfa Romeos prepared in the workshop on Viale Trento e Triste in Modena.

The National Automobile Museum summarizes the story in four words: «In 1929 he founded the Scuderia Ferrari in Modena, a sports club whose program is for its members to participate in as many races as possible. The main supplier of cars is Alfa Romeo for which Ferrari takes care of the development of racing models, participation in races, and the transfer of accumulated experiences to series production. An official racing team was soon created (1931) which made use of very famous drivers such as Nuvolari, Varzi, Campari, Borzacchini and many others. Six years later Alfa dissolved Scuderia Ferrari (of which it had acquired the majority of the shares) in favor of a new sports structure called Alfa Corse from which, however, due to internal disagreements, Enzo Ferrari left two years later. In 1940 Ferrari founded Auto Avio Costruzioni in Modena and created just two examples of the 815, an original 8-cylinder 1500 cc designed by Alberto Massimino. During the Second World War the workshop was moved from Modena to Maranello where Ferrari developed an unprecedented 12-cylinder V engine which was the basis for the construction of the 125S, the first model to bear the Ferrari name.”

It is the beginning of the history of Ferrari, the public side of Enzo Ferrari, a man whose dark glasses, worn even indoors, shield his sometimes angular reluctance. His difficult relationships with journalists to whom he reluctantly indulges and by whom the team, even at the top of its fortunes, is often accused of reticence is well known: proof of this is a page of Tuttosportof 19 May 1977 which collects correspondence between the then director Gian Paolo Ormezzano, who publishes his own letter to Enzo Ferrari of whom he is a friend, and even ghost-writer, in which he asks him to account for the difficulties in which he put his colleagues and the related response. And to say that as a young man Ferrari had also practiced and dreamed of journalism a bit, one of his first passions like operetta. Upon his death Ormezzano wrote about The Press: «In Maranello it drove drivers and journalists, kings and billionaires, divas and artists crazy. Feeling controlled by destiny and at the same time its controller (-puppeteer- he told us one day), he played a lot with others. But it was the game of a great man, of a genius, therefore a game that was never dishonest.”

Enzo Ferrari is not born mythological, he becomes one, his life is marked by hard moments: a racing accident in Guidizzolo during the 1957 Mille Miglia, which killed the driver De Portago and eleven spectators, cost him a long odyssey to prove his correctness in court.

That very story is reconstructed in the film Ferraridirected by Michael Mann and released in theaters in 2023, broadcast on Rai Due on 16 February at 9.20pm.

For the 1957 Mille Miglia episode, Ferrari was initially accused, according to Treccani’s reconstruction, «of not having equipped the car with tires suitable for the speeds developed. In October 1958 in an article published in Civiltà Cattolica, signed by Father. Azzolini, A useless massacre: speed car races, the Ferrari was defined as a modern Saturn that devours its own children. The Modena entrepreneur, however, managed to convince his accusers of his innocence. He was acquitted in the investigation for the Mille Miglia accident, while Azzolini, persuaded by him, recognized that the responsibilities of the races had to be attributed to the organizers and to those who held public powers”.

Just a year earlier he had lost Dino, his son, to a degenerative disease: three lights with the colors of the flag under his portrait remembered himin the rooms of Enzo Ferrari, who became Commander, but not yet an engineer honoris causa something that he would become later, when honorary degrees were a very rare commodity.

He sometimes had visceral relationships with the Ferrari drivers, some he loved, others he respected, a question of character, even his own. He had a predilection for the daredevils: Tazio Nuvolari, his first true hero – later set to music by Lucio Dalla –above all. Ferrari said of him: «He dreamed of getting on par with death».

But also Gilles Villeneuve, which came from snowmobiles, on which he bet, against all evidence, by going fishing in Canada: a lost bet if sport were only calculated mathematics and calculable on the abacus of measurable victories and defeats.

Gilles Villeneuve, father of Jacques, future world champion, won just six grand prix in Formula 1 with Ferrari and wrecked more than one car – without the Drake breathing fire, forgiving him the impossible – before going to die in one of the rare times in which he wasn’t looking for it: on the Zolder circuit in Belgium on 8 May 1982. But his driving style was already legend and death fueled it. The legacy of visibility and love that the flying Canadian Gilles Villeneuve brought to Ferrari was incalculable, out of proportion to the race results.

Ferrari preferred the imaginative ones to the calculators, on the track, and off it he acted like them, the creativity was also in his management style, as a headhunter. Alessandro Colombo, his personal assistant, recalled upon his death: «He was immediate, he wanted what he wanted immediately, he was not a long-term programmer». Able to respond: “Colombo, we are not the Holy See that can afford to make plans for millennia, we here must act quickly.”

When Enzo Biagi asked him, in a children’s book from the Seventies entitled And you know it?, «Why does man want to win, he replied: «We were born with an anxiety to overcome and ambition leads us to excel. Rivalry, even cruel, is already in the beginnings of human history: Cain and Abel, and in the tales of myths: the hardships that Hercules can endure, or in fairy tales: where there is always a girl who asks in the mirror who is the most beautiful in the kingdom. From an early age we meet the best in class, the one who climbs best in the gym, the one who skates with the most elegance. And from the first contact with others, the instinct of comparison and emulation emerges. There are, of course, the fighters, the lukewarm, the absent.”

And when Biagi wanted to know who his sympathies went to, he replied: “Obviously to those who fight.”

He fought until he was 90 years old, living in suspense about the future, convinced that he had to prove every time that the previous result was deserved. For those who saw him from the outside he was the Great Old Man or the Drake. From the inside, no one knows: he kept it to himself.