Sergej Bulgakov.

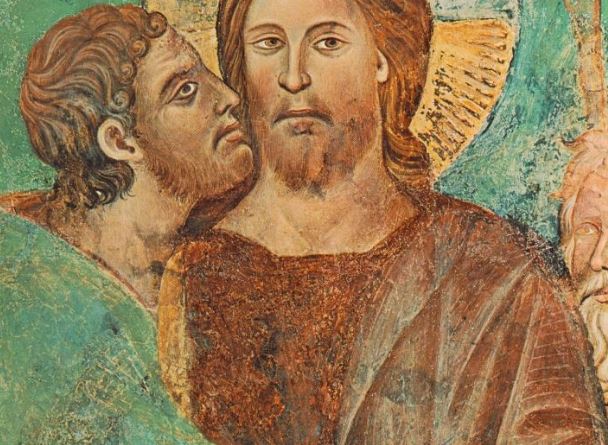

Who was Judas Iscariota really? The disciple who betrayed Jesus for thirty denarii, or the man who lost himself in a mystery greater than him? To try to answer is Sergej N. Bulgakov, one of the greatest theologians of Russian Orthodoxy of the twentieth century, with a book for the first time available in Italian: Judah Iscariota. The traitor apostle (EDB, 144 pages, 18.50 euros), with the translation and care of Lucio Coco.

Published for the first time in Russia in the 1930s, the essay is an all -field reflection that holds together evangelical exegesis, speculative theology and psychological investigation. Bulgakov is not satisfied with the easy condemnation: digs in the figure of Judah with respect and restlessness, trying to understand its tragedy. “Judas’ tragedy – he writes – is not only that of man who despair of God’s forgiveness”, but becomes a symbol of the conflict between man’s freedom and the unfathomable design of providence.

For Bulgakov, Judas is not a mere instrument of divine will, nor a simple traitor blinded by greed. He is rather a man dominated by an obsessive idea of the kingdom of God, convinced – perhaps – that delivering Jesus meant accelerating the messianic advent. “Judas expected a completely different messiah”, and her gesture – in the vision of the theologian – was born from an irremediable clash between human expectations and divine plans.

The heart of Bulgakov’s reflection is all in the most difficult question: was Judah free? If betrayal was necessary for salvation, how far can it be said to be responsible? “If God creates man free, how to think this freedom in the case of Judah?” Asks the theologian. His inner drama is consumed when he realizes that Jesus will not react, he will not be saved, and above all he will not forgive him. But is it really the case?

“Judas does not even touch him the idea of the forgiveness of Christ – writes Bulgakov -. His despair leads him to believe that the Mercy of the Lord, who even forgiven his crucifixors, would stop in front of his gesture ». This is where the book touches the summit of its tragic intensity: Judas damn because it cannot accept that you can be saved.

Far from both demonization and forced rehabilitation, Bulgakov’s book delivers a deeply human portrait of Judah to the modern reader. Not a monster, not a martyr, but a man in which the great dilemmas of the Christian faith are reflected: freedom, fault, forgiveness, destiny.

A powerful and necessary work, capable of making us reread the Gospel with new eyes, and to put that part of us bare who fears that he is never enough to deserve mercy. With the lucidity of the theologian and the sensitivity of the writer, Bulgakov accompanies us on a journey into the middle of the night, where the light of forgiveness seems unattainable – yet he continues to shine.