Schulim Vogelman with his daughter Sissel, who died in Auschwitz

In the famous list that allowed the Nazi industrialist Oskar Schindler to save the lives of over a thousand Jews, there was also an Italian, Schulim Vogelmann, who, despite his name, lived and worked in Florence and who, while he and his family were trying to reach the border with Switzerland, he was captured and sent to Auschwitz. An incredible story, that of Schulim Vogelmann, which we asked his son Daniel, founder of the Giuntina publishing house, to tell us. specialized in texts on Jewish history, narrative and tradition.

«My father never told me much about his past. I knew he had been to Auschwitz, but I didn’t know the role Oskar Schindler had played in his salvation. I discovered this many years after his death (which occurred in 1974 when I was 26), after the release of the film Schindler’s list. A friend called me to tell me that my father’s name was also on the list of Jews on the list, which appears at the end of the film. I wrote to Yad Vashem, the national Holocaust remembrance body in Jerusalem, and they confirmed to me that he was indeed one of the Jews saved by Oskar Schindler.”

The story of Shulim Vogelmann starts from afar: on April 28, 1903 Schulim was born on a train who brought his parents, Nahum Vogelmann and Sissel Pfeffer and their eldest son Mordechai, from Tarnopol to Przemyslany, both cities in eastern Galicia, a region of Poland that was then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Daughter Miriam then arrived to complete the family. The father had a small bank, they were a wealthy family: the children studied at the Jewish religious school and in the summer they went on holiday to Grado, in Italy. With the outbreak of the First World War, many Galician Jews were deported to Siberia by the Russians and the Vogelmann family took refuge in Vienna, where they had to adapt to a more modest standard of living. After the premature death of her mother, at the end of the war the family split: her father and Miriam returned to Poland, Mordechai went to Zurich to study as a rabbi, Schulim, who was only 15 years old, went to Palestine. But it was difficult to find work there and after serving in the English Army he was reunited with his brother, who in the meantime had gone to Florence to teach Talmud in a rabbinical college. He was hired in the Giuntina printing house of which he became the director at the age of 25. In 1933 he married Anna Disegno, the daughter of the rabbi of Turin, and in 1935 their daughter was born who was called Sissel like grandma. A happy family that only three years later began to suffer the effects of the racial laws. Anna lost her teaching job, Sissel was expelled from school. Their story is similar to that of many other Jews. Despite the persecution, the Vogelmanns were confident that nothing serious would happen and continued to remain in Florence. Only when there was a raid in the Rome ghetto did they decide to flee to Switzerland with false documents. By train they arrived in Sondrio, where in a bar someone noticed that they were Jews and reported them. They were sent back to Florence to the Villa La Selva internment camp and after a few weeks they were transferred to the San Vittore prison in Milan where, on January 30, 1944, they left on cattle cars headed for Auschwitz from the infamous platform 21 of the Central Station. Liliana Segre and her father were also on the same train. After six hellish days of travel, upon arrival Schulim saw his wife and daughter for the last time. Only later did he learn that from the train they had been sent directly to the gas chambers. «My father was spared because despite being “old” according to Auschwitz criteria (he was 41 years old), the documents listed him as a printer. He was thus transferred to the Plaszow camp where the Nazis had begun printing fake pounds with the aim of bankrupting the Bank of England. And from there, thanks to his knowledge of Polish, he managed to get himself sent to Schindler’s factory, thus ending up on the famous list that allowed Oskar to transfer “his” Jews to Brünnlitz, Czechoslovakia. On May 9, 1945 they were freed.” Having returned after a long and tiring trip to Florence, Schulim, during an evening for the Hanukkah celebration in 1946, he met a widow, Albana Mondolfi. With her four-year-old son Guidobaldo she saved herself by hiding in a nuns’ compound. They married and in 1948 Daniel was born.

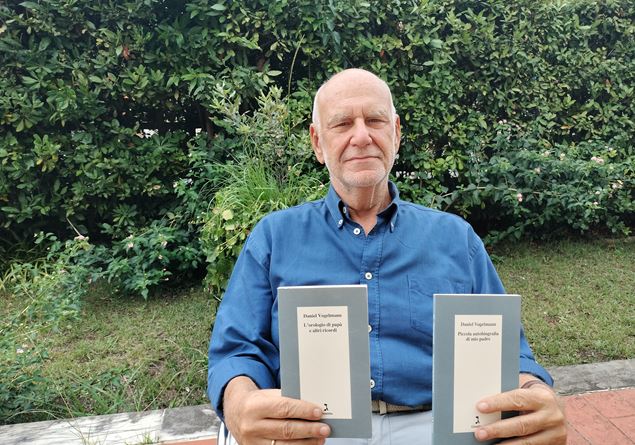

«I have always considered my dad elderly. He worked a lot and didn’t have much time to play with me. He had become the owner of the printing house and had made it grow. He loved life, he was optimistic despite what he had been through and when they asked him where he studied he replied: “In Auschwitz”. A few years after his death, in 1980, I decided to transform the printing house into a real publishing house. The first book I translated and published under the Giuntina brand was The night by Elie Wiesel, future Nobel Peace Prize winner. Now my son Shulim (yes, like my father but without the c) has taken over the management of the publishing house. My granddaughters Alma and Shira always ask me about Sissel, that beautiful little girl taken from life at just 9 years old. The little sister I never met and to whom I dedicated some little poems like this one: “You must have been really dear to God/ if he wanted you with him so soon./ But then tell me, you who perhaps know everything:/ we, not him are we dear?”.