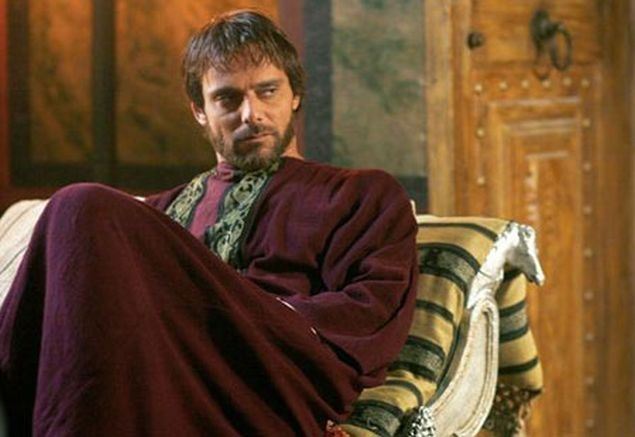

(In the photo, the actor Alessandro Preziosi plays Saint Augustine in the fiction broadcast on RaiUno)

A Doctor of the Church, a Bishop, a philosopher, but first of all a man, with his frailties, his contradictions and his constant search for a profound meaning to life. The figure of Saint Augustine (whom the liturgy commemorates on August 28) is always extraordinarily current, a spiritual beacon who has guided the lives of thousands of believers (and not only) of all eras and latitudes. Few other personalities of the Christian universe have left over the centuries a legacy comparable to his. “You created us for yourself, Lord, and our hearts are restless until they find rest in you.” This famous phrase, contained in the Confessions, can in a certain sense exemplify the entire life of this saint, animated by an incessant yearning for truth.

Augustine was born in Tagaste (in present-day Algeria) in 354. His father, Patrick, belonged to a pagan family, while his mother Monica was a fervent Christian: the Catholic Church venerates her as a saint. The maternal figure had a central importance in Augustine’s education: he himself states in his writings that he drank the name of Jesus with milk and that he was included, since childhood, among the catechumens. But with adolescence his insatiable, restless and somewhat rebellious spirit took him down very different paths. During a long period of study between his hometown and Carthage, he became a scholar of philosophy and rhetoric, experiencing the pleasure of excelling over others thanks to a formidable intellectual readiness, bordering on genius. In those years he also undertook an unruly lifestyle, dedicated to the pleasures of the body.

His studies led him to learn about Manichaeism, a religious movement of Persian origin that preached the presence in the world of two opposing principles of good and evil, both divine. The young man was bewitched: he became a regular visitor to the sect, first in Carthage, then in Rome, where he moved at the age of 29. Over time, however, that initial infatuation gave way to disenchantment: the Manichaean doctrine did not satisfy Augustine’s scientific curiosity, nor did it provide answers to the questions of his soul, which had become increasingly pressing. Thus, progressively, he distanced himself from it.

In 384 he settled in Milan and it was there that the great transformation took place, that of his life: the meeting with the bishop Saint Ambrose reawakened in him the Christian faith that had been dormant for so many years. And he understood that he had finally met what his spirit had always sought: he received baptism from Ambrose. In that period he reconnected with his mother, an inexhaustible source of inner wealth. Memorable were the conversations, some of which were later transcribed in the Confessions, that the two had in Cassiciaco (near Milan), then in Ostia: they were moments of profound intensity and spiritual harmony. After Monica’s death, which occurred suddenly in 387, Augustine returned to Africa, determined to undertake a monastic life. Having sold his possessions, he founded a small community, living initially in his native Tagaste, then in Hippo.

But once again his life took an unexpected course. He was in fact proclaimed bishop by popular acclamation (a rather frequent practice in those times: the vox populi was held in high regard because it was considered the voice of God). Thus, although it had not been his choice, Augustine accepted, proving himself to be an enlightened bishop and becoming a point of reference for the African churches. After many years of assiduous and tireless care of souls, he became seriously ill and after a few months, while his land was besieged by the hordes of Vandals, he died. It was 430. His rule of life was the model for various religious experiences, among which the Order of Augustinians stands out, spread throughout the world.

The corpus of writings of this Doctor of the Church is very vast and articulated: it ranges from philosophical works to apologetic ones in defense of Christianity, such as De Civitate Dei (The City of God), from dogmatic to moral, from biblical to pastoral. Particular effort was then devoted by the Bishop of Hippo to the refutation of heresies, to which he dedicated many texts and a large part of his life. There is, however, one work that, more than all the others, has been able to impress itself on the collective conscience: these are the Confessions, written around 400. In this work Augustine retraces the history of his long interior torment and thoroughly probes his life, with acumen but also with a frank style, without fear of revealing errors, falls and youthful deviations. The autobiographical nature of this text makes it accessible to everyone and not only to theologians.

And even today The Confessions are a compass for many men and women in search. « Late have I loved you, Beauty so ancient and so new, late have I loved you – we read between the pages of the book – Yes, because you were inside me and I was outside: there I sought you. Deformed, I threw myself on the beautiful features of your creatures. You were with me, but I was not with you. Your creatures kept me away from you, nonexistent if they did not exist in you. You called me, and your cry broke through my deafness; you flashed, and your splendor dispelled my blindness; you spread your fragrance, I breathed and now I yearn for you; I tasted you and now I hunger and thirst for you; you touched me, and I burned with desire for your peace ».