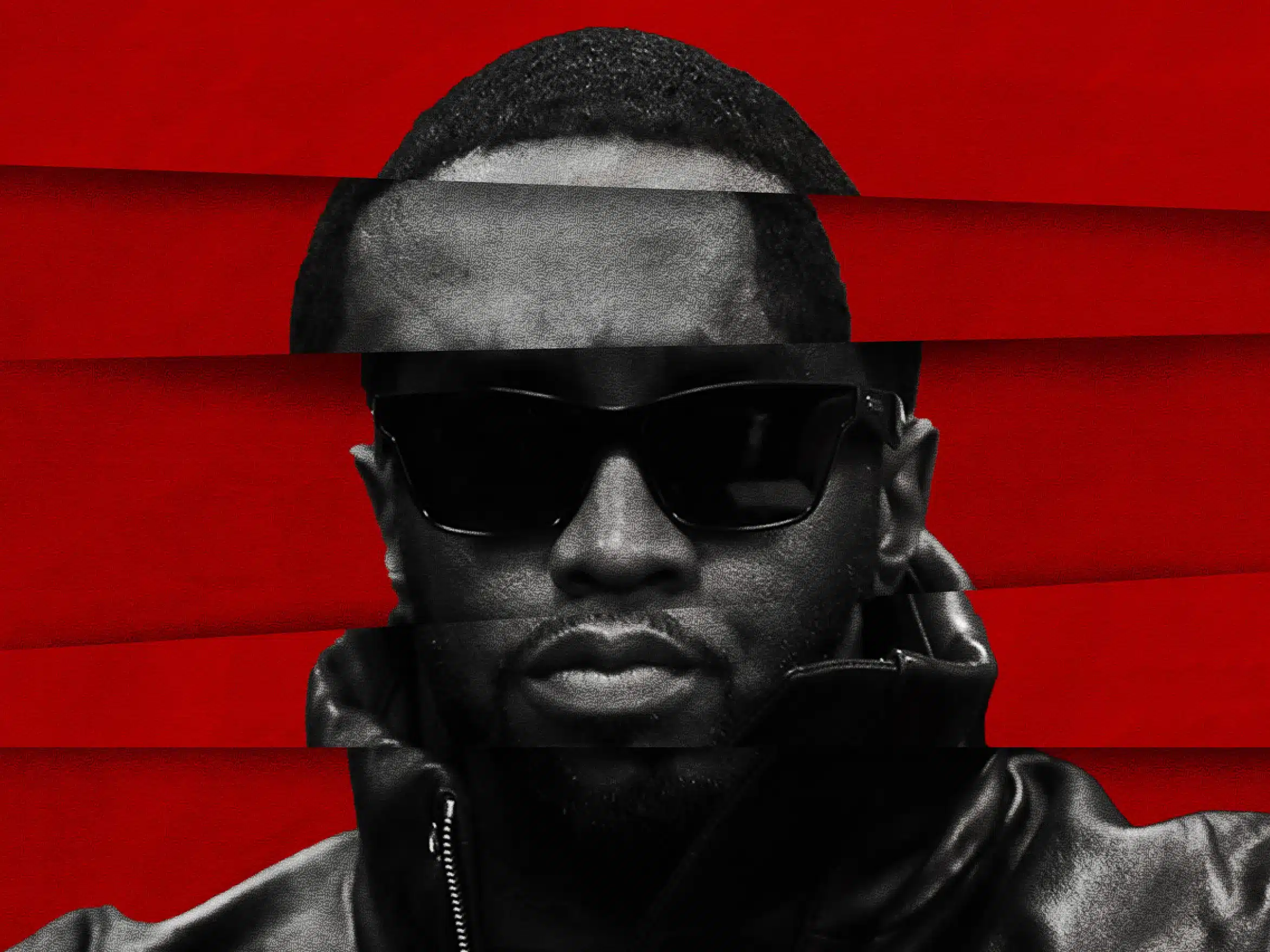

Sitting on the couch, I watched as Juror 75, a middle-aged Indian man clad in a white button-up, explain his decision not to indict Sean “Diddy” Combs on two sex-trafficking counts.

“He’s beating her, and then the next minute, they’re going on dinner and trips,” he said on Sean Combs: The Reckoning. “It’s like going back and forth, back and forth. If you don’t like something, you completely get out. You cannot have both ways. Have the luxury and then complain about it? I don’t think so.”

I wanted to tell this man this is a textbook case of domestic violence, the building of tension, then explosion, followed by reconciliation called the “Honeymoon Phase,” before the next storm. However, the jurors failed to see this. They misconstructed staying in an abusive relationship as justifying one. We need juries that are educated on trauma and how it impacts relationships and even court testimonies.

Cassie Ventura met Combs at 18. They were introduced by Ryan Leslie, who discovered Cassie, produced her hit single “Me & U,” and then played it for Combs.

Combs was directly responsible for Cassie’s initial career success. He was her boyfriend and boss at the same time, and this power dynamic persisted throughout their relationship. During her testimony, Cassie asserted that Diddy controlled virtually every aspect of her life, including how she dressed, her career, and her finances. Domestic violence is a pattern of behaviors used to gain or maintain power and control.

“No victim wants to be abused,” Dr. Dawn Hughes said. “They stay in the relationship because it’s not just about hitting. It’s about a lot of abusive behaviors that make a victim feel trapped.”

Last September, Combs was accused of racketeering, two sex-trafficking counts, and two counts of transportation for prostitution. The jury found him guilty of transporting Cassie Ventura and an anonymous victim known as “Jane” to places where they would participate in sex acts and prostitution. But he was acquitted of all other charges. He was never going to be convicted of racketeering, the most serious charge, which carries a potential life sentence. To convict Combs on this charge, prosecutors would need to prove that the rapper had coordinated with his network to commit multiple crimes over several years. According to the Human Trafficking Institute, “only 5% of active sex trafficking cases involved exploitation directed by gangs or more formal organized crime groups.”

The surprise, however, was that Diddy was found not guilty of two sex-trafficking counts despite the jury being shown explicit video of the ‘freak-offs’ and Diddy’s abuse. Juror 160 admitted Combs’ violent behavior toward Ventura after watching the video where he punches and kicks her as she waits for the elevators before dragging her down the hall into their hotel room. But domestic violence wasn’t a charge in the case, she said in the documentary. Since his behavior couldn’t be packaged into the charges presented, he was dismissed.

But domestic abuse can establish the dynamics for trafficking. Data from the National Human Trafficking Hotline shows that 39% of sex trafficking victims were trafficked by an intimate partner. Rarely are victims kidnapped by strangers, and often it occurs within the context of relationships. The jury didn’t see this coerced dynamic because they believed Ventura consented by being in a relationship with Diddy. They either didn’t know or didn’t consider that, on average, it takes 7 attempts to leave an abusive relationship.

According to the Justice Department, nearly 80 percent of rapes and sexual assaults go unreported due to shame, fear of not being believed, or self-blame, making it one of the most underreported crimes in the US Our legal system enforces this stigma, encouraging the feedback circuit by underenforcing these crimes. While partner rape is illegal in all 50 states, many loopholes either shorten sentences or exempt spouses/partners from being prosecuted. These cases often require shorter timeframes for reporting the assault, proof of a higher degree of force than other rape cases, and even dismissal of charges where the person is incapacitated.

Ventura’s treatment by the jury validates this statistic. Her relationship with Combs and her emotional state while testing made jurors believe she wasn’t telling the truth. They never considered how traumatic it was for her to relive the incident in a courtroom with your perpetrator staring at you, working with the defense to undermine your testimony.

Relevant context, including trauma, isolation, and coercion, is rarely considered in courtrooms. Trafficking and domestic violence are not solely physical and sexual abuse; abusers can intimidate, name call, limit interaction with the outside world, minimize and shift responsibility for abusive behavior, prevent access to work, exercising many forms of power and control over relationships. Multiple research findings reveal that jurors hold misconceptions about rape and rape victims. In 2020, 25 of 28 studies found that verdicts were influenced by jurors’ false beliefs about rape. Jurors who started deliberations accepting prejudicial myths about abuse, assault, and rape were likely not going to change their minds despite the evidence presented.

The criminal legal system already deters many people from coming forward. To end this cycle, we need to reform our system to ensure jurors are understanding and compassionate about the realities survivors endure. If not, we will continue to silence victims and subject them to additional harm.

About the Author: Farah Merchant is a digital strategist, writer, and a Public Voices Fellow of The OpEd Project, the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Justice, and the Every Page Foundation, working to advance justice through storytelling.