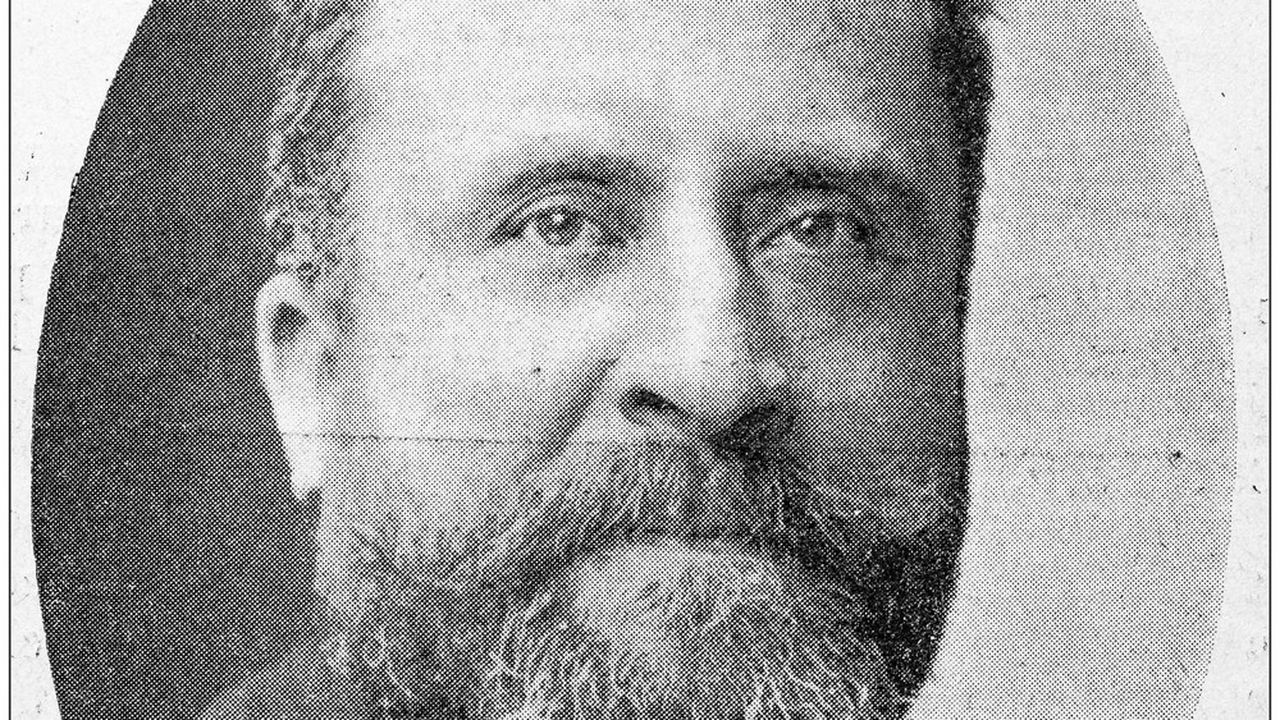

Exactly 110 years ago, Jean Jaurès was assassinated at the Café du Croissant in Paris by Raoul Villain, a nationalist activist. Three days later, France was thrust into the First World War. At a time of conflicts in Yemen, Gaza, the Sahel, Syria, and, for the past two and a half years, the return of war to Europe with the fighting in Ukraine – which has already claimed hundreds of thousands of victims – Jean Jaurès serves in France as the absolute reference for pacifism. And as an unstoppable argument of authority for politicians of all stripes, who quote him at will to make him say one thing or the other.

“Jaurès assassinated a second time”, lamented the communist Fabien Roussel on March 8, reacting to the intervention of the Macronist Nathalie Loiseau who affirmed that “peace in Ukraine is not possible today” and that it would amount to “a capitulation”.

“Jean Jaurès must be screaming in his grave!”

“In fifty years, we will talk about Jean-Luc Mélenchon as we talk about Jean Jaurès today,” says the rebellious MP Eric Coquerel, saluting his boss’s “non-aligned” bias, just a few days after the start of the large-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine. “Jean Jaurès must be screaming in his grave!” Yannick Jadot then replies. “Can you imagine Jean Jaurès defending the bombing of civilian populations in Syria? Can you imagine Jean Jaurès defending the assassination of political opponents in Russia? Can you imagine Jean Jaurès defending war crimes?”

15 years ago, the FN candidate in the European elections, Louis Aliot, also dared to use a quote from the socialist, decontextualized, on his campaign posters: “To those who have nothing left, the homeland is their only possession.” Jean Jaurès is also cited in the founding principles of the NPA: “capitalism carries war within it like a cloud carries a storm.”

The reappropriation of the figure of the socialist reached its peak during the European election campaign, with Raphaël Glucksmann (PS-Place publique) and Manon Aubry (LFI) citing him to justify, for the former, aid to the Ukrainian resistance, for the latter, the need for an immediate ceasefire – “Jaurès said that we do not wage war to get rid of war”. But then, what did Jean Jaurès really say about war?

“Not absolute pacifism”

Jean Jaurès “fights for peace and rejects war as a means of settling disputes,” says Gilles Candar, president of the Jaurèsian Studies Society and author of Peace speech published by 1001 Nights. But the socialist MP does not defend “absolute pacifism: he is not someone who absolutely refuses war in all circumstances,” the historian qualifies.

Because Jean Jaurès grew up with a brother, an uncle, and cousins who were military men. “It is the French family that has the greatest number of admirals, even today,” says Gilles Candar. “The commission in which he was most involved was the War Commission,” “one of his great works is The New Armywhere he reflects on what the army of a democratic France should be like”, and “one of his great speeches is on the number of ’75 cannons’ per company”… despite his image today as an inflexible anti-militarist, and even if he “still hopes for a pacifist development”, Jean Jaurès “knows well that war can come, thinks about it and prepares for it”.

“Neither absolute peace nor absolute war” for the Tarn MP, who envisages “legitimate wars”, the historian emphasizes. Those for “national defense”, if France is attacked, and those for the idea of ”defending the fundamental interests of humanity”, in particular if “a people is threatened with extermination”: “at the time of the great Armenian massacres by the Turkish empire, he speaks of an intervention, which could be a military intervention, to avoid what he calls a ‘war of extermination'”.

What would Jean Jaurès have thought of his permanent recuperation by the political class? “Jaurès would surely have said to be wary of the Jaurès of quotes,” laughs Gilles Candar. “Lapidary phrases” or “simplifying formulas” were not for the socialist. The tribune complicated, nuanced, in interminable speeches, which he sometimes had to say in several parts in the Chamber in order to finish them.

“Two Facets of Jaurès”

Thus, for Gilles Candar, the favorite quote of the rebels and the communists “we do not make war to get rid of war” is “incomplete and dangerous”. If the exercise is perilous and anachronistic, Jean Jaurès, in view of his positions, would probably have defended in Ukraine “peace negotiations which are not done on any basis and which must obtain the support of the parties involved. Not a peace which would be the daughter of defeat or constraint. Otherwise it would be a fragile peace which prepares revenge”, believes the historian.

To Raphaël Glucksmann, who quotes Jean Jaurès to justify aid to the Ukrainian resistance, the socialist could have pointed out that “war must always reflect on what it proposes as a way out of peace. What peace is envisaged? What balance can be found afterwards?”, judges Gilles Candar. In the end, “the speeches of one and the other are not illegitimate, they are two facets of Jaurès,” the specialist decides.