Mario Draghi’s report on “the future of European competitiveness” was submitted to the European institutions on Monday. In some 400 pages, the former president of the European Central Bank deciphers the challenges of a European Union that has fallen behind the rest of the world, particularly the United States.

Before proposing solutions, the document makes a worrying diagnosis: Europe is accumulating delays, as shown by the figures for growth, foreign trade, investments and even labour shortages.

· Slowed growth

Europe’s growth failure has been apparent over the past two decades, and has been worsening over the past decade. In 2002, US GDP was 17% higher than that of the European Union. The gap has now reached 30%.

If we reason in terms of purchasing power parity, the figures are a little less spectacular but the trend is the same: we go from a differential of 4% in favor of Europe in 2002, to a gap of 12% in favor of the United States in 2023.

“The main driver of these divergent developments is productivity,” the report stresses: Europe’s lower productivity explains 70% of the gap in GDP per capita between the two sides of the Atlantic. The consequences are felt in the standard of living: real income per capita has increased “almost twice as much in the United States as in the EU since 2000,” the document points out.

Three external factors “that supported growth in Europe after the end of the Cold War” have diminished. First, world trade, which flourished during the first twenty years of the century, largely supported the European economy. But international trade is now growing less quickly. Secondly, with the end of Russian gas, Europe is deprived of a relatively cheap source of energy. Thirdly, the end of geopolitical stability is forcing the Twenty-Seven to increase their defence spending.

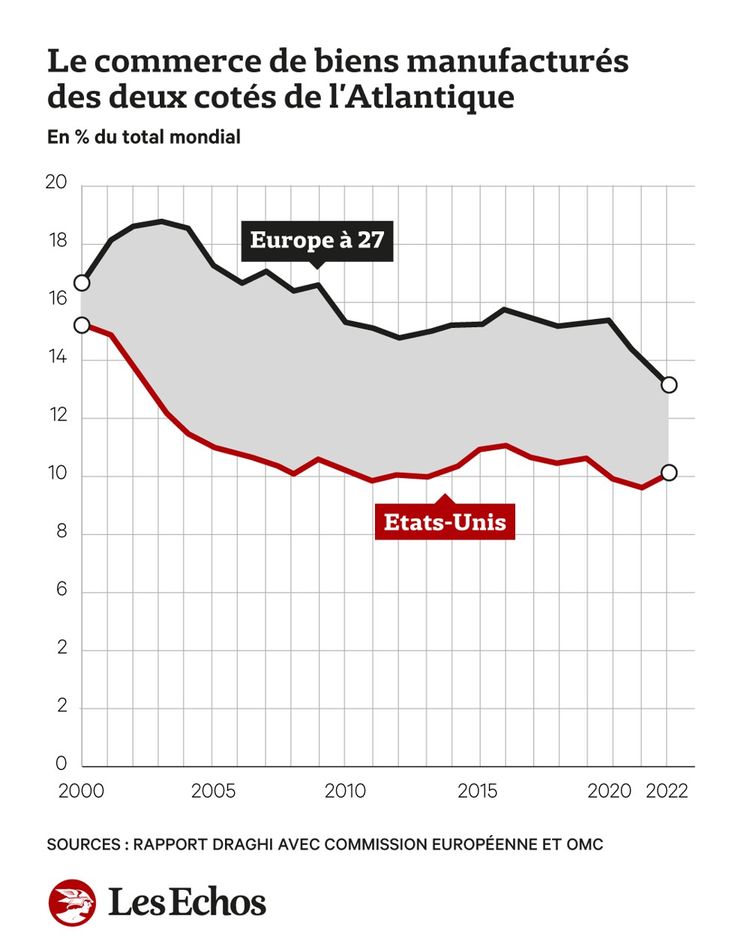

· Foreign trade in decline

The European Union’s share of global trade is “declining, with a notable drop since the start of the Covid pandemic”, Mario Draghi’s report notes. The Twenty-Seven’s share of global trade has fallen by three points since 2000, while China, at the same time, grew by 13 points.

The United States saw its commercial power collapse at the beginning of the century – much more than that of Europe – but its share in world trade then stabilized, and has even risen slightly since 2020.

European foreign trade is under double pressure. On the one hand, European companies are suffering from less buoyant global demand, particularly from China.

On the other hand, they are facing increased competition from Chinese companies on world markets: today, nearly 40% of the Eurozone’s exporting industrial sectors are in direct competition with Chinese companies; this share was only 25% in 2002.

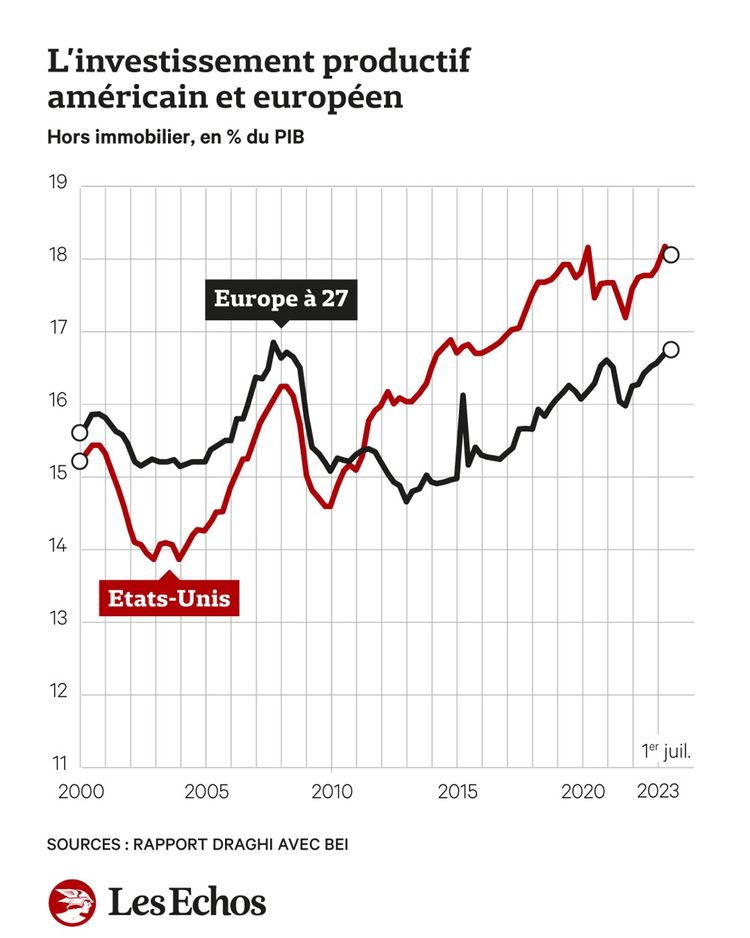

· Insufficient investments

For a long time, Europeans invested more than Americans, supporting innovation and growth. The situation reversed about ten years ago and the gap widened rapidly. Today, investment represents more than 18% of GDP in the United States, compared to around 16.5% in the EU.

This is due in particular, the report stresses, to the technological backwardness of Europeans. In the United States, the top three private investors at the beginning of the century were in the automotive and pharmaceutical sectors. In the 2010s, investment leadership shifted to IT. Today, digital technology dominates.

“In contrast, the European industrial structure has remained static” during this period: the top three companies investing on the Old Continent are still car manufacturers. “In Europe, investment has remained concentrated on mature technologies and in sectors” where productivity growth is slowing.

American companies spend twice as much as their European competitors on research and innovation, relative to the GDP of the two blocs, representing an investment gap of 270 billion euros per year.

The lack of dynamism in European industry is explained “in large part” by the weaknesses of innovation which prevent new sectors and challengers from emerging, says the Draghi report.

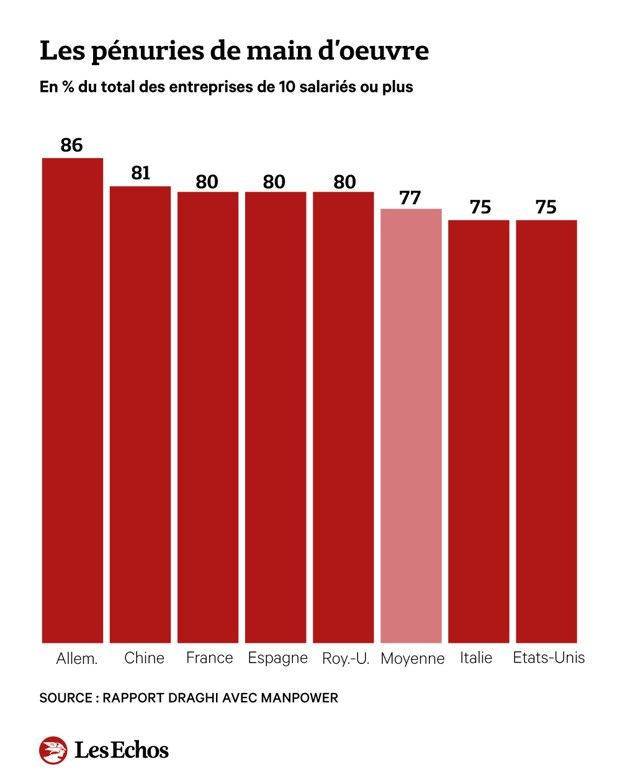

· A worrying shortage of labor

All developed countries are hit by labour shortages, but the problem is even more acute in Europe. More than 85% of German companies are unable to recruit the necessary staff, as are 80% of French and Spanish companies. In the United States, this share is also high (75%) but lower than the world average.

The problem is “particularly acute” in Europe because demographic change will reduce the working population, which is not the case on the other side of the Atlantic. If current migration flows are maintained, the European working population would fall from 264 million people today to 223 million in 2070, or 41 million fewer workers. The decline would be twice as great (87 million) without the help of immigration.

In Europe, the shortage of labor concerns both skilled and unskilled jobs. The problem has worsened since the Covid epidemic and has reached peaks in the hotel and catering industry, information technology and construction.

The education system is partly responsible for some sectors. For example, Europe has only 850 graduates in science and technology subjects per million inhabitants, compared to more than 1,100 in the United States. In addition, the Old Continent is suffering from a brain drain due to more numerous and interesting professional opportunities abroad. “More than 60% of EU companies say that the lack of talent is a major barrier to investment,” the report notes.