by Sergio Casali

While for the first time in its history the Volkswagen closed some factories and the steel giant Thyssenkrupp fired thousands of employees a few weeks ago Süddeutsche Zeitungone of the main German newspapers, came out with a very impactful headline: «The fear of poverty has become socially explosive».

Because Germany, historically the “locomotive of Europe”, is the first European economy in terms of GDP size it is today the only advanced country to find itself facing a recessionand this is not only the cause of the political upheavals that shake the country, but also the reason for underground tremors that pass through German society and bring out ancient ghosts. The Germans call it Abstiegsängste, “fear of decline”, a fear that only partly relates to real data, but above all concerns something deeper and unconscious.

And it is perhaps this fear that we need to look at, if we want to interpret the reasons for the space that the far right is finding in the political preferences of Germans.

The topic was addressed by Felicitas Hillmann – sociologist who mainly deals with migration and integration at the Institute of Urban and Regional Planning of the Technische Universität of Berlin – during the Italian-German dialogue meeting “Living as an excluded” organized by the Goethe Institut a Genoa on November 19th as part of the “Shared Looks” cycle.

Although Germany is one of the richest countries in the world, almost 18 million German citizens (21% of the population) are poor or are on the verge of becoming so. Children, pensioners, single parents and people with a history of migration are especially at risk of a life of insecurity and social exclusion: in 2023, over 22% of migrants were at risk of poverty.

«In a society in crisis and marked by heavy inequalities, however – explains Hillmann – there is not only the material side of poverty, but also the emotional and subjective one: people fear that they will no longer be able to participate in social life, that they do not have the means, that they will have to depend more and more on the State. This is what led to the spread of the far right».

The fear of decline is measured in two dimensions, explains the sociologist: «firstly, as fear of losing one’s job, fear of immediate personal decline, then as fear of medium or long-term decline, concern for one’s own future financial situation, fear that the pension will not be sufficient to live with dignity”.

German society is crossed by great contradictions: on the one hand, a huge need for manpower, on the other, growing unemployment in the traditionally leading sectors of the German economy. «These ambiguities must be explained – states Hillmann – also by helping people not to demonize migrants, to create inclusive societies that do not isolate anyone. The only antidote to fear is to talk to others, to dialogue, so as not to remain only in the bubble in which we are used to living.”

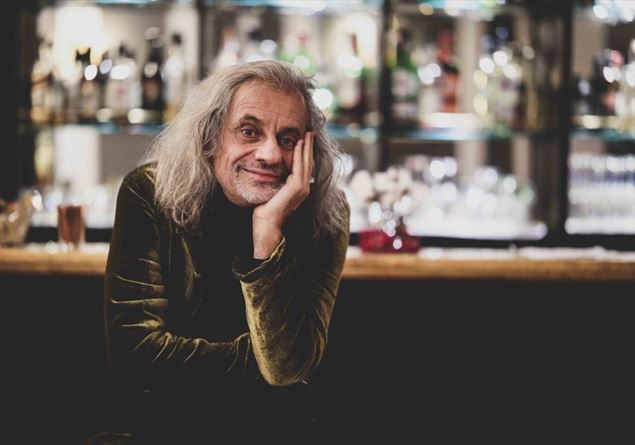

And it is precisely this antidote that it also hooks onto Mario Marazziti, historic exponent of Community of Sant’Egidiowho does not struggle to find very close analogies with the Italian situation in the condition of the most vulnerable in Germany “even if with a few years of delay”. «The fact however – he explains – is that what scares is not so much the real problem, for example immigrants, but the fear of losing one’s status: this is what allows populism to advance».

What is needed, then, is a “counter narrative”: «We need to simply tell the truth and that is that fear can only be fought by integrating and that, where society becomes welcoming, not only does it not lose its identity, but on the contrary it rediscovers its roots and reclaims the great European history. We need to build communities, because it is in solitude that fear ferments and there are fears that restrict the space of democracy.”