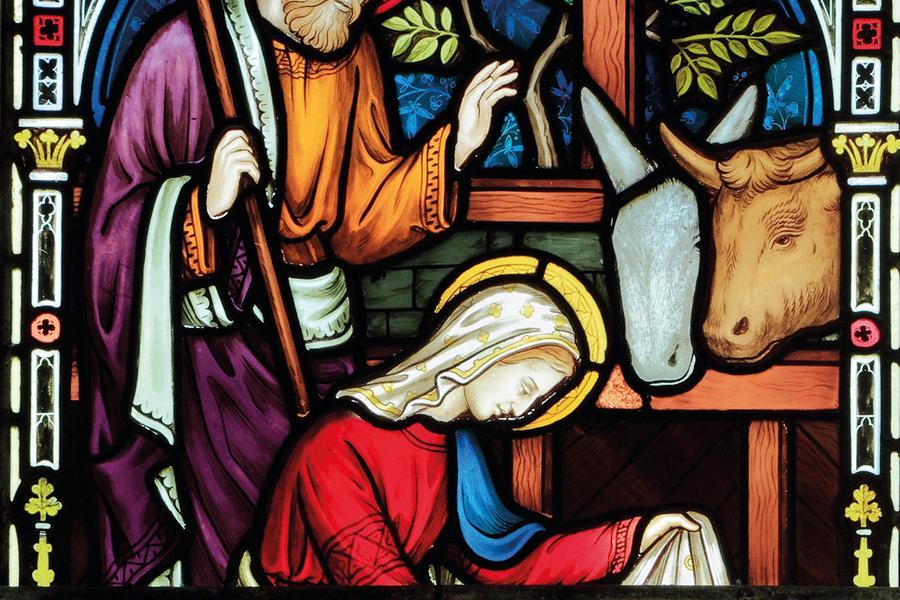

The humble wisdom of the ox and the donkey

Among the figures that permanently inhabit our nativity scene, the ox and the donkey occupy an emotional and almost inevitable place. But Luke does not mention them and neither does Matteo. The evangelical scene of the birth is very sober; neither a stable nor a cave appears, but only a word that recurs insistently, to mark the place of the event: the manger. There is an essential poverty of detail. Where, then, do the ox and the donkey come from? Not from the desire to fill narrative gaps, nor from the desire to make the scene more realistic. The origin is much older and theologically articulated and was born from listening to Scripture in the liturgy of the first centuries, when the Christian community meditated on the beginning of the book of Isaiah in the days immediately preceding Christmas.

The prophet, at the beginning of his book, launches an accusation against the ingratitude of the people: “The ox knows its owner and the donkey its master’s manger, but Israel does not know, my people do not understand” (Isaiah 1.3). It is a verse of great symbolic power: animals recognize those who feed themwhile man loses the memory of his God. When this text was listened to together with the Lucanian story – where the child is placed in a manger – the connection was immediate. In Latin Isaiah says: asinus novit praesepe domini sui. The word praesepe“crib”, is the same one that Christian tradition would later choose to designate the birth scene.

From this linguistic and theological closeness the intuition was born: next to the Child placed in the meadow of his humility, the animals were placed which, according to Isaiah, they know how to recognize their Lord. The ox and the donkey are therefore a visual commentary on the Scripture, a silent preaching that speaks in contrasts: animals understand what often escapes humans. They are not decorative elements, but prophetic figures. In the nativity scene, their presence asks the viewer to understand: the Lord is here, he nourishes you, he offers himself to you. Do you recognize him? The patristic tradition then enriched the symbol with further nuances. The ox, an animal of sacrifice in the temple of Jerusalem, has been read as representation of Israel, the community of promise and messianic expectation. The donkey, considered unclean in ancient legislation, has become the symbol of the peopleof distant peoples, of those who did not yet know the God of Abraham. In the nativity scene, therefore, these two animals are together like images of all humanity: those who belong to the history of Israel and those who come from remote horizons, both gathered around a Child who comes for everyone. Significant, then, is the posture with which Christian art has depicted them: not lying in an attitude of repose, but in an alert, almost adoring position. It is the created world that recognizes its origin; it is the humble and daily reality that senses the presence of its Lord.

These ancient symbols are not foreign to our time. Today, more than hostility towards the Gospel, distraction weighs heavily: a sort of anesthesia of the gaze that accustoms us to everything and makes us no longer recognize anything. Christmas proposes Isaiah’s question again: what are we capable of really recognizing? The frenzy of the holidays, the lights, the commitments can transform into a large manger that no longer nourishes: everything is full, and yet everything remains empty.

The nativity scene, with its disarming calm, is there restores the ability to see. Christmas does not ask us to fill the scene, but to recognize what gives life. In front of a manger, a God who makes himself small continues to seek our amazement.