In a garment factory outside Dhaka, Bangladesh, a 19-year-old worker stopped showing up. Her supervisor said she had left. Her coworkers whispered she had reported him for harassment. There was no investigation. No grievance mechanism. Yet the factory passed its compliance audit with flying colors.

Despite billions spent on audits to prevent human rights abuses, cases like this are routinely overlooked. In 2023 alone, companies spent nearly $38 billion on ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) audits – a figure expected to reach $65 billion by 2027. These assessments, designed to reduce reputational, legal, and operational risk, typically track issues like wages, hours, and child labor – all important, no doubt.

But amid all this scrutiny, they rarely ask the most basic question: Are women safe?

Gender-based violence (GbV) refers to any act of physical, sexual, or psychological harm rooted in gender inequality. In global supply chains, it takes many forms: verbal harassment, sexual coercion, retaliation for speaking up, or domestic violence that affects a worker’s attendance or performance.

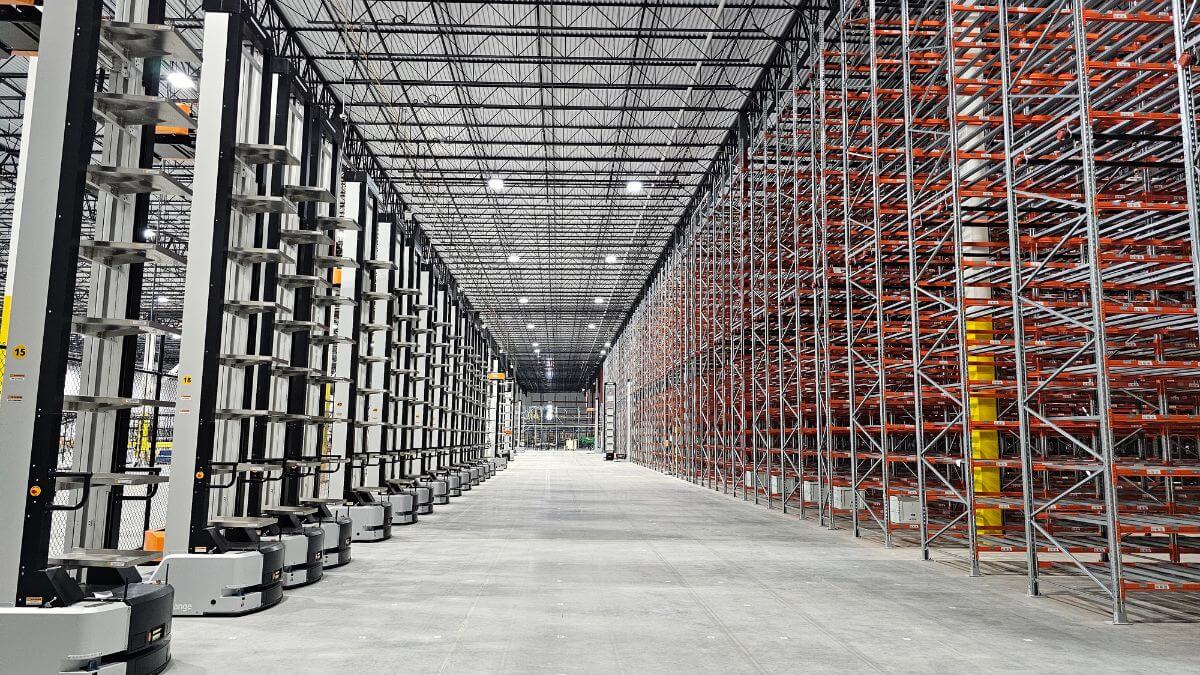

It happens on garment factory floors in Bangladesh, in warehouses across the US, in migrant worker camps in the Gulf, and in the informal waste-picking sector in Latin America. It disproportionately affects women of color, migrants, informal workers, and gender minorities. It is rarely documented, let alone addressed.

In India’s sugarcane fields, for example, where women perform grueling physical labor for long hours, seasonal migrants, some married as early as 12, are undergoing routine hysterectomies to avoid menstruation, pregnancy, or illness that might cost them a day’s wage. Local surveys found hysterectomy rates as high as 36 percent, compared to a national average of 3 percent. This is gender-based violence by another name: industrialized abuse disguised as survival.

In Lesotho, women in factories supplying jeans for major global brands like Levi’s and The Children’s Place reported routine sexual coercion – supervisors demanding sex in exchange for keeping their jobs. Very few filed complaints. The reasons were painfully predictable: fear of losing their jobs, stigma from coworkers, or retaliation from supervisors. The abuse was so widespread it prompted international headlines, yet the factories had passed multiple audits. Many workplaces, especially in low-wage sectors, lack even the most basic protections such as anonymous reporting channels or trauma-informed HR systems.

And the US is not disconnected. Thanks to the global nature of supply chains and the sheer scale of this unregulated abuse, much of what we consume today is quietly tainted by gender-based violence.

Despite the scale of harm, GbV isn’t even part of most audit checklists. In my fifteen years of working on gender-based violence across factories, farms, and informal sectors, I’ve seen how GbV not only erodes lives, but also guts entire supply chains: from rising turnover and fractured teams to stalled production and workers quietly disappearing from the system.

What companies must do now:

First, they must add GbV indicators to ESG and audit frameworks. At a minimum, these should include questions about harassment, assault, and accessible reporting channels. Second, they should invest in gender-sensitive grievance mechanisms that are anonymous, multilingual, and trauma-informed. Third, supervisors and audit teams must be trained in gender sensitivity, power dynamics, and psychological safety.

But real change goes beyond metrics. It means funding and listening to survivor-led or grassroots organizations that already have the trust, insight, and lived experience to design what actually works. It means treating violence as violence – not a PR risk.

Granted, with today’s complex tariff regimes and shifting regulations, companies face real pressures: compliance fatigue, geopolitical uncertainty, and the constant push for profit. But it’s worth remembering that forced labor was once considered ‘out of scope’ for corporate audits, too. That changed only after expositions, lawsuits, and legislation like the UK’s Modern Slavery Act forced companies to trace labor practices more rigorously. The same conditions that enable forced labor – economic desperation, opaque oversight, and entrenched hierarchies – also fuel gender-based violence. In fact, they often overlap.

If a company is serious about ethical sourcing, it cannot afford to treat GbV as an optional extra.

Some institutions, such as the International Finance Corporation and the Ethical Trading Initiative, have already begun piloting gender-safety frameworks. But unless mainstream companies follow suit, GbV will remain an invisible crisis inside so-called “ethical” sourcing.

The next time you see a label that reads “ethically made,” ask yourself: Were the women behind it safe?

Supply chains are human chains. When they’re built on silence and readiness, they collapse. Addressing gender-based violence is not charity. It’s justice. And it’s long overdue.

Because no audit, certification, or ESG report is credible if it ignores more than half the workforce.

About the Author: Mathangi Swaminathan is the Founder & CEO of Parity Lab, whose mission to end the cycle of gender-based violence in one generation. She is an Echoing Green Fellow, a Public Voices Fellow, and a policy researcher recognized by Harvard’s Jane Mansbridge Award.