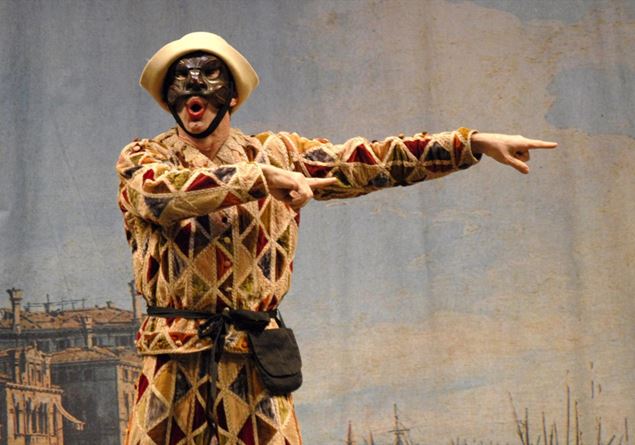

Arlecchino and Pantalone (photo by Diego Ciminaghi)

Harlequin is perhaps one of the most recognizable Italian masks in the world. Its origins are lost between medieval popular rituals and the tours of the Commedia dell’Arte, crossing centuries and borders. But it is in the twentieth century, directed by Giorgio Strehler, that his face returns to embody a universal theatre: Harlequin servant of two masters, debuted on 24 July 1947, it became the symbol of the Piccolo Teatro and an international phenomenon for over fifty years. Arlecchino therefore continues to change, to reflect the eras and cultures that welcome him. It is this capacity for metamorphosis, more than tradition itself, that inspired the new project born between Milan and Yaoundé: Njangui – Toujours Ensemble!a traveling theater workshop, promoted by the Italian Embassy in Cameroon and Piccolo, which last September brought together twenty artists from Cameroon, France, Germany, Italy and Spain. The underlying idea is simple but powerful: use the Harlequin mask as a meeting tool, as a figure capable of welcoming and mixing different cultures. From this perspective, the connection was born with a Cameroonian concept, the njangui: a word that in one of the local languages indicates a form of mutual exchange, a community collection that allows small economic activities to be started. «It’s a system of mutual trust», says director Stefano De Luca. «When someone wants to start a business but has no funds, they launch a njangui: each person in the village contributes a small sum to support it. It is an economy that arises from the bottom, from human connections, not from the banks.”

In Cameroon, njangui is more than an economic system: it is a practice of daily solidarity, a way of thinking about relationships. Unlike the individualistic logic that dominates many Western societies, survival here is based on mutual trust and mutual support. The individual does not assert himself alone: he grows together with the community that supports him. It is from this principle that the European group took inspiration reinvent Harlequin and the other masks of the Commedia dell’Arte in a collective key, as tools of dialogue and not of representation. The laboratory was thus transformed into a space of exchange: a “theatrical njangui” where each artist shared their own language, their own voice, their own memory.

From this meeting a street performance was born. The plot is simple: Arlecchino and Pantalone set off in search of a treasure said to be hidden in Africa. After many meetings, they discover that the real treasure is not gold but the ability to share, to support one another, to build together. Harlequin, mask of the poor, the servants, the excluded, immediately recognizes the value of the gift; Pantalone, miser and master, struggles to accept it.

The political allegory is clear, but it doesn’t stop at the message: the strength of the show lies in the way in which it brought opposing worlds into dialogue. The performance was brought both to the poorest neighborhoods of Yaoundé and to the French school in the capital, attended by a small local elite. “There is barbed wire around the school, there are walls,” says De Luca, “but barefoot children arrive in the street, the noise of ox carts, life coming into the picture.”

The meeting between Harlequin and the njangui is not just an exercise in cultural diplomacy: it is a political gesture, a small concrete utopia in which the theater returns to being what it was at its origins, a form of community. “No one had ever done something like this for us,” said the residents of the neighborhood. Perhaps this is where we need to start again: from the living body of the people who watch, respond, participate.

Stefano De Luca will now take care of the re-proposal of l‘Harlequin servant of two masters at the Piccolo Teatro, until November 2nd..