Anxiety linked to aging parents often affects those aged 40-65.

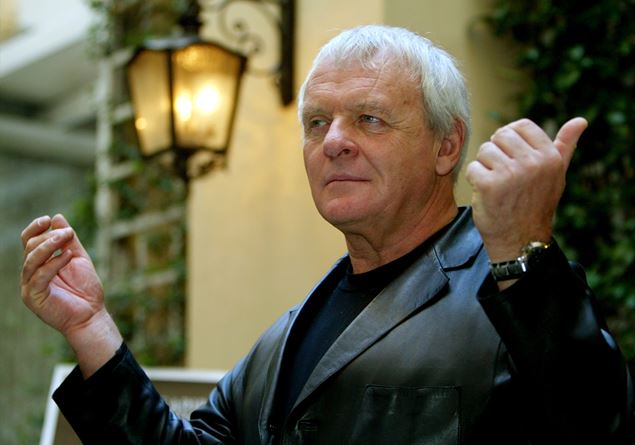

We don’t see time passing, until the day we read it in the wrinkles of our parents. Anxiety linked to aging parents often affects those aged 40-65. In fact, accepting the aging of one’s parents, especially the mother, the one we have always seen as an “invincible” figure, is one of the most intense emotional challenges of adult life. “However, we must say that there are 1001 ways to age and that aging is the gentlest. Loss of autonomy is not a necessary step and there is no need to mourn this image if no signs of fragility appear. The real urgency is rather to realize that this “figure which seems eternal” will no longer be one day and to take advantage of it while we can.“, immediately underlines Dr Bruno Oquendo, geriatrician, creator of the @le_gériatre account on Instagram and author of the book “My parents are getting old” (ed. Vuibert).

To better cope with the aging of your parents, the geriatrician advises reinventing the relationship. “Aging must be seen as a continuum and not as a decline. Over time, our relationships naturally change with our parents. We can decide to spend more time together, to take an interest in the history of our loved one, to share activities, but above all it is a personal and intimate connection. Why not offer new “family rituals” of discovery together, meals together…“, suggests the geriatrician.

The situation is different when autonomy declines or a chronic illness sets in,The child must trigger “mourning for the idealized object”: it is useless to deny that our loved one is getting older and has limits. On the contrary, the grieving process begins with the recognition of this reality. Talking, writing or doing psychotherapy can help digest this abrupt “awakening”, especially if feelings of guilt or anger emerge. The geriatrician also highlights the concept of “white mourning” which occurs with neurocognitive diseases (such as Alzheimer’s). “The loved one remains there physically but is no longer really them.” Caregivers then experience “ambiguous grief” because the person is alive, but the relationship and personality have disappeared. In all cases, to manage anxiety about the future and fear of imminent loss, he emphasizes the need for “social support” (friends, psychologists, caregiver groups) and recommends “plan, ask questions about possible choices (succession, etc.) to feel more like an actor than a spectator“.

Faced with the refusal of help often encountered (for example, the mother who “minimizes her difficulties”), the geriatrician advises adopting the posture of “partner” and not of “inverted parent”: the objective is to seek an alliance while avoiding frontal shock. For this, it is preferable to “ask open questions, avoid judgment, reformulate the parent’s needs before immediately offering a solution and seek a common goal (like going out to see the grandchildren)“. It is often more effective to get help from a health professional, because the message often gets across better when it is not the child who is carrying it.