San Carlo Borromeo is a central figure in the ecclesiastical and civil history of the sixteenth century whose work, especially for Milanhas overcome the force of oblivion. He is the patron saint of catechists and bishops. The emblem is the pastoral staff.

Biography: born to a noble family, he became cardinal at 22

Born in 1538 in the Rocca dei Borromeo, on Lake Maggiore, he was the second son of Count Giberto and therefore, according to the custom of noble families, he was tonsured at 12 years old. A brilliant student in Pavia, he was then called to Rome, where he was created cardinal at 22.

He founded an Academy in Rome according to the custom of the time, called the “Vatican Nights”. Sent to the Council of Trent, in 1563 he was consecrated bishop and sent to the Chair of Saint Ambrose of Milan, a vast diocese that extended across Lombardy, Venetian, Genoese and Swiss lands. A territory that the young bishop visited in every corner, concerned with the training of the clergy and the conditions of the faithful.

He founded seminaries, built hospitals and hospices. He used the family wealth for the benefit of the poor. He imposed order within the ecclesiastical structures, defending them from the interference of the local powerful.

A work for which he was the target of a failed attack. During the plague of 1576 he personally cared for the sick. He supported the creation of institutes and foundations and dedicated himself with all his strength to the episcopal ministry guided by his motto: «Humilitas». He died at the age of 46, consumed by illness on 3 November 1584.

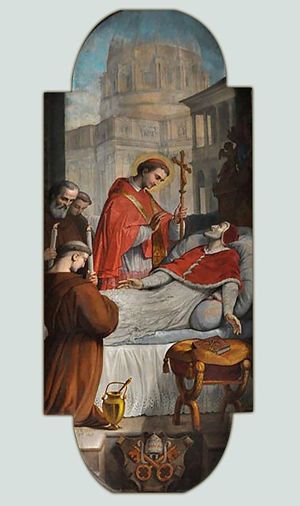

Orazio Borgianni, San Carlo Borromeo

Career in Rome

In the case of Pius IV we find ourselves faced with a rare case of positive nepotism for the Church. The Pope immediately promoted his two nephews: Federico (1561) had the position of general captain of the Church, Carlo, not yet twenty-two years old, was appointed cardinal cot a position that today we could call Secretary of State.

Shortly afterwards he also entrusted him with the administration of the diocese of Milan with the obligation to remain… in Rome. And this wasn’t the only charge. He had several others with the inevitable accumulation of their respective economic benefits. Historians say that the agreement between Pope and nephew was always perfect. Despite his roles, Carlo always remained a man of culture.

To this end he founded a humanistic-literary academy, made up of friends, called Notti Vaticane. He had also bought himself a sumptuous palace with servants following, in which he organized sumptuous and festive receptions. Those were the times: all this not out of vanity but because he considered it appropriate for the position he held and for the fame and decorum of the family he came from.

The death of his brother Federico and the new life of penance

The sudden death of his brother Federico (1562) made him radically change his life. He interpreted it as a sign from God to reform his life even more in an evangelical sense. So it changed radically: goodbye to festive receptions, goodbye to even morally legitimate entertainment, goodbye to the Vatican Nights which became a cenacle of religious culture. He reduced his standard of living, intensifying penance, fasting and renunciations.

He also resumed, with more commitment, his theological and pastoral training. He was still bishop of a diocese even if he did not practice directly. The Pope was perplexed by the ascetic transformation of his precious nephew (whom he sometimes called “my right eye”).

He shook his head: it all seemed exaggerated to him. He even went so far as to scold him (blaming his excessive ascetic zeal on the advice of his spiritual directors and the influence of contemporary figures of the caliber of Ignatius of Loyola, Gaetano da Thiene, Filippo Neri: all Saints). The Pope discouraged him, rebuked him, but let him do it, and in the end he imitated him.

Saint Charles assists his uncle Pius IV on his deathbed

The “director” of the Council of Trent

But Carlo Borromeo’s greatest merit was convince the Pope to reconvene the Council of Trent suspended in 1555. If this worked so hard and well and if it ended gloriously and profitably for the Church (1563) the great merit went to Charles. He was its organizing mind and inspirer. In July 1563, he was ordained a priest and shortly afterwards a bishop.

He wanted to be a pastor of souls in his diocese of Milan and was waiting for the opportunity. The Council was over but it was necessary to make sure that the successor of Pius IV also had the intention of continuing the reform that had resulted from it. Carlo believed in the action of the Holy Spirit in the direction of the Church, but, at the same time, he did humanely what he himself thought useful.

In fact, he suggested the names of the new cardinals of the future conclave to his old and sick uncle: it had to promote only those favorable to the reform of the Church desired by the Council of Trent. Having done this, he asked him to be able to preside, as papal legate, the provincial council which was held in Milan (his diocese) to implement the conciliar provisions.

Uncle Pope agreed. And Carlo left. But a short time later he had to hastily return to Rome (in the company of Filippo Neri) because the Pope was now at his end. In fact, Pius IV died in his arms on 9 December 1565.

An “iron shepherd” for Milan

In April 1566, he reached Milan, where he immediately began the great work of reform according to the Council of Trent. He was a brilliant organizer and a tireless worker, so much so that Filippo Neri exclaimed: “But this man is made of iron”. He organized his diocese into 12 districts, oversaw the revision of the life of the parish by obliging the parish priests to keep archive records, with the various activities and parish associations.

He put a lot of effort into the training of the clergy by creating the major and minor seminary. Above all, he was tireless in visiting the populations entrusted to his pastoral and spiritual care, starting his first visit in 1566 immediately after arriving in Milan.

His visit to a parish was prepared spiritually with prayer and preaching which was to lead to the sacraments. At the beginning the bishop held a meeting with the notables of the town to whom he asked among other things: “How do the parishioners behave in church? Are there heretics, usurers, concubines, bandits or criminals? Are there sowers of discord, parishioners who do not observe Lent?… Do family men educate their children well? Isn’t there exaggerated luxury in men’s and women’s clothing? If there are charitable and social aid institutions, are they well administered?”. And other similar questions. As you can see concrete.

The triumphal entry of San Carlo into Milan in the painting by Filippo Abbiati

The attack of 1569 for his plan to reform the Order of the Humiliated

San Carlo encountered difficulties and sometimes even hostility. As in the case of the attack he suffered on 26 October 1569 by four friars of the Order of the Humiliated. One of these shot him while he was praying in his private chapel. Reason? Borromeo wanted to reform that now decayed religious order. But the proposed reforms were seen by the Humiliati as humiliations. The bullet pierced his spool, but he remained miraculously unharmed and the people interpreted it as a sign from above of the goodness of his reforms. And the Humiliated, in name, were also humiliated in fact and forever with their definitive cancellation.

But the depth of his personality as a shepherd and of his greatest love who “gave his life for his friends” was shown on the occasion of the plague of 1576. Absent from the city because he was on a pastoral visit, he returned immediately, while the Spanish governor and the grand chancellor fled away. He immediately made his will knowing that the plague had no regard for anyone, not even the high clergy: he organized the assistance work, personally and courageously visited those affected by the terrible disease, helped everyone tirelessly to the point of earning a rebuke from the Pope of Rome.

Despite all the pastoral activity, Borromeo made four trips to Rome and four to Turin. He was very devoted to the Holy Shroud. It was precisely in 1578 that the Dukes of Savoy brought her to Turin so that the bishop of Milan, who had asked to venerate her personally, would be spared the difficult and dangerous crossing of the Alps (official reason), but also to defend her from the desires of the French (reason political). The exhibition of the relic in Turin in 1978 was to commemorate his arrival in the city.

Due to his non-stop pastoral activity, frequent travel, and continuous penances, his health rapidly deteriorated.

Death caught him very prepared on November 3, 1584, and his cult spread rapidly until his canonization in 1610 by Paul V.

Carlo Borromeo died physically but his legacy of personal holiness and tireless action for the Church was more alive than ever, and would continue through the centuries. Until today.