“We should ask ourselves what excesses the people of the Middle Ages would have gone, if this big and sweet voice had not risen.”

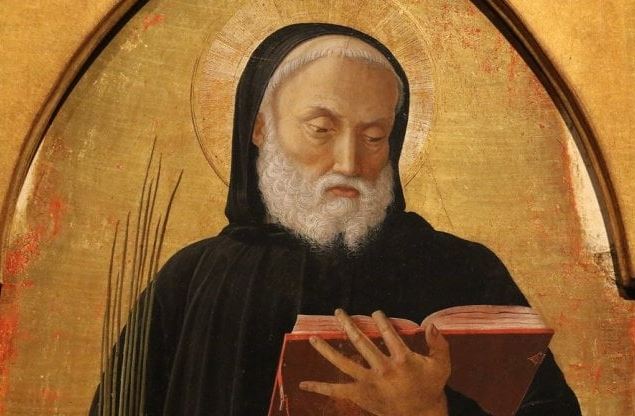

To say it was the historian Jaques Le Goff. The voice is that of San Benedetto da Norciathe patriarch of western monasticism. After a period of solitude at Subiaco, he moved to the cenobitic form before a Subjacus and then a Montecassino.

His Rulewhich summarizes the oriental monastic tradition by adapting it with wisdom and discretion to the Latin world, opens a new way to the European civilization after the decline of the Roman one. In his “school” the meditated reading of the Word of God and the liturgical praise, alternating with the rhythms of work in an intense climate of fraternal charity and mutual service have a decisive role.

In the furrow of San Benedetto, centers of prayer, culture, human promotion, hospitality for the poor and pilgrims arose in the European continent. Two centuries after his death, there will be more than a thousand monasteries guided by his rule.

For this in 1964 Paul VI He proclaimed him patron of Europe. He died in Montecassino (Frosinone) on March 21 between 543 and 560 but the church solemnly remembers him on 11 July.

To his biography, Pope Benedict XVIwho was inspired by him to choose the name as a Pontiff, dedicated the general hearing of April 9, 2008.

The Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI during a general hearing

Benedetto tells Benedetto: the birth

The birth of San Benedetto is dated aroundyear 480. He came, so says San Gregorio the Great, “ex Nursiae province” – from the Nursia region. His wealthy parents sent him for his training in studies in Rome. However, he did not stop in the eternal city for a long time. As a fully credible explanation, Gregorio hints at the fact that the young Benedict was disgusted by the lifestyle of many of his companions of studies, who lived in a dissolute way, and did not want to fall into their same mistakes.

He wanted to please God alone; “Solo Deo Placere Desiderans” (II Dial., Pest 1). Thus, even before the conclusion of his studies, Benedetto left Rome and retired into the solitude of the mountains to the east of Rome. After a first stay in the village of Effide (today: Affile), where for a certain period he associated himself with a “religious community” of monks, he made herself in the non -distant subjacus.

There he lived for three years completely alone In a cave that, starting from the early Middle Ages, constitutes the “heart” of a Benedictine monastery called “Sacro Speco”.

The period in Subiaco, a period of solitude with God, was for blessed a maturation time. Here he had to endure and overcome the three fundamental temptations of every human being: the temptation of self -affirmation and the desire to place himself in the center, the temptation of sensuality and, finally, the temptation of anger and revenge.

It was in fact belief of Benedetto that, only after winning these temptations, he could have told others a useful word for their situations of need.

And so, having re -scrutinized his soul, he was able to fully control the drives of the ego, to be thus being a creator of peace around him. Only then did he decide to found his first monasteries in the Anio Valley, near Subiaco.

The Abbey of Montecassino

From Subiaco to Montecassino

In the year 529 Benedetto left Subiaco to settle in Montecassino. Some explained this transfer as an escape in front of the intrigues of an envious local ecclesiastical. But this attempt at explanation proved to be not convincing, since the sudden death of him did not industry blessed to return (II Dial. 8).

In reality, this decision imposed on him because he had entered a new phase of his inner maturity and his monastic experience. According to Gregorio Magno, the exodus from the remote Valle dell’Anio towards Monte Cassio – a hill that, dominating the vast surrounding plain, is visible from afar – has a symbolic character: Monastic life in hiding has its own raison d’etre, but a monastery also has its own public purpose in the life of the Church and societymust give visibility to faith as a life force.

In fact, when, on March 21, 547, Benedetto concluded his earthly life, he left with his rule and with the Benedictine family he founded a heritage that has brought over the centuries and still brings fruit all over the world.

Between prayer and research of God

Entirely second book of Dialogues San Gregorio Magno It illustrates how the life of San Benedetto was immersed in an atmosphere of prayer, the bearing foundation of its existence. Without prayer there is no experience of God. But Benedetto’s spirituality was not an interiority outside reality. In the restlessness and confusion of his time, he lived under the gaze of God and precisely so he never lost sight of the duties of everyday life and man with his concrete needs. Seeing God understood the reality of man and his mission.

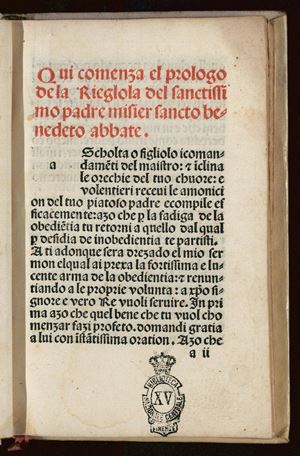

In his rule he qualifies the monastic life “a school of the service of the Lord” (prol. 45) and asks his monks who “the work of God (that is, to the divine office or the liturgy of the hours) is not placed anything” (43.3).

He underlines, however, that Prayer is primarily an act of listening (prol. 9-11), which must then translate into the concrete action. “The Lord awaits that we respond every day with the facts to his holy teachings”, he says (prol. 35). Thus the life of Munich becomes a fruitful symbiosis between action and contemplation “so that God” (57.9) is glorified in all.

In contrast with an easy and self -centered self -employment, often exalted today, The first and indispensable commitment of the disciple of San Benedetto is the sincere search for God (58.7) on the path traced by the humble and obedient Christ (5,13), To the love of which he must not put anything (4,21; 72.11) and just like that, in the service of the other, he becomes a man of service and peace.

In the exercise of the obedience implemented with a faith animated by love (5,2), the monk conquers humility (5.1), to which the rule dedicates an entire chapter (7). In this way man becomes more and more in accordance with Christ and reaches true self -registry as a creature in the image and likeness of God.

The prologue of the rule

The rule: “God reveals the best solution to the youngest”

The disciple’s obedience must correspond to the wisdom of the abbot, which in the monastery keeps “the sieves of Christ” (2.2; 63,13). His figure, outlined above all in the second chapter of the rule, with a profile of spiritual beauty and demanding commitment, can be considered as a self -portrait of Benedetto, since – as Gregory the Great writes – “”The saint could not in any way teach differently from how he lived“(Dial. II, 36).

The abbot must be together A tender father and also a severe teacher (2.24), a real educator. Inflexible against vices, however, it is mainly called to imitate the tenderness of the good shepherd (27.8), to “help rather than dominate” (64.8), To “accentuate more with the facts than with the words everything that is good and holy” and to “illustrate the divine commandments with its example” (2,12). To be able to decide responsibly, the abbot must also be one who listens to “The Council of the Brothers” (3,2), because “often God reveals the best solution to the youngest” (3,3).

This provision surprisingly makes a rule written almost fifteen centuries ago! A man of public responsibility, and even in small areas, must always be a man who knows how to listen and knows how to learn from what he listens.

Benedetto, an example for today’s lost Europe

Benedetto qualifies the rule as “minimum, traced only for the beginning” (73.8); In reality, however, it offers useful indications not only to the monks, but also to all those who seek a guide on their journey towards God. Due to its measure, its humanity and its sober discernment between the essentials and the secondary in spiritual life, it has been able to maintain its illuminating strength to date.

Paul VIproclaiming in October 24, 1964 San Benedetto patron of Europeintended to recognize the wonderful work carried out by the saint through the rule for the formation of European civilization and culture.

Today Europe – just released for a century deeply wounded by two world wars and after the collapse of the great ideologies that revealed as tragic utopias – is looking for its identity. To create a new and lasting unit, political, economic and legal tools are certainly important, but it is also necessary to arouse An ethical and spiritual renewal that draws on the Christian roots of the continent, otherwise Europe cannot be reconstructed.

Without this lifeblood, the man remains exposed to the danger of succumbing to the ancient temptation to want to redeem himself – Utopia who, in different ways, in the twentieth century Europe caused, as Pope John Paul II pointed out, “An unprecedented regress in the tormented history of humanity“(Teachings, XIII/1, 1990, p. 58).

Looking for real progress, we also listen to the rule of San Benedetto today as a light for our journey. The great monk remains a true teacher to whose school we can learn the art of living true humanism.