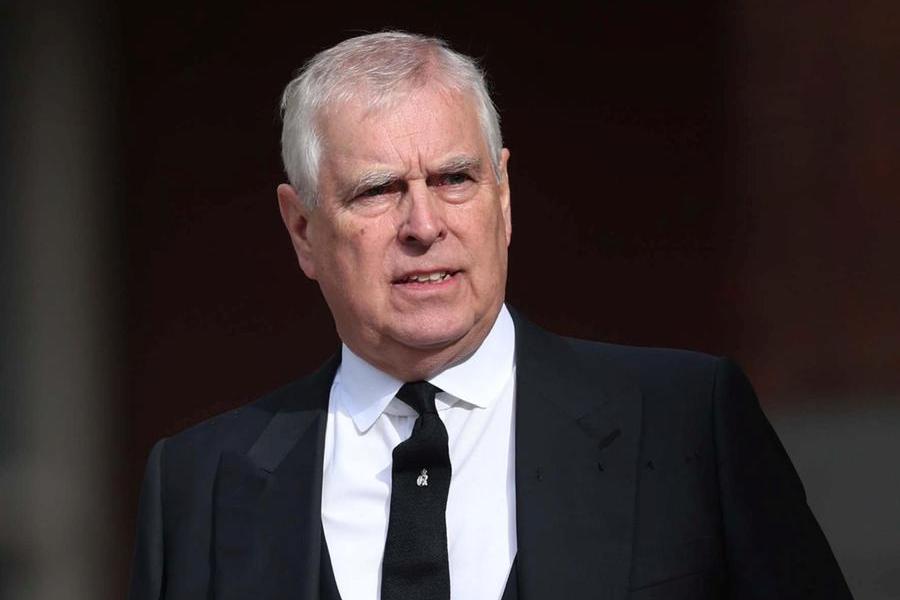

It is a sentence that closes a dark chapter in the recent history of South Korea and, at the same time, opens one of reflection for the entire democratic world. On February 19, the Seoul court held Yoon Suk-yeol, former President of the Republic, sentenced to life imprisonment, found guilty of leading an armed insurrection and abuse of authority. The prosecutor’s office had even requested the death penalty. The former Defense Minister Kim Yong-hyun was also sentenced with him, accused of having collaborated in organizing the coup: for him, thirty years in prison.

Yoon’s story is, in a sense, the story of a man who has lost touch with reality. And the cause, at least in part, is to be found in a phenomenon that should make us all reflect: the radicalization through far-right YouTube channels.

It all started one night in December, when South Koreans were awakened by a television announcement from their president. Yoon Suk-yeol, in office since 2022, declared a state of emergency and imposed martial law, a measure that had not been adopted in the country for over forty years. In a solemn tone, he accused the opposition of being infiltrated by “pro-North Korean communist forces” and announced that the army would take control of the country. In the same hours, a group of special forces raided the headquarters of the National Electoral Commission, the body that manages the elections. The soldiers took some photographs and left, finding nothing. It was the clearest sign of the absurdity of what was happening: a military raid based on nothing, ordered by a president convinced by conspiracy theories that had no foundation.

Parliament reacted with surprising speed. Within a few hours, all the political forces, including Yoon’s own party, voted unitedly to cancel martial law. The authoritarian adventure ended before dawn. But the damage was done: South Korea had experienced the longest night of its modern democracy.

The trial and sentencing

In the following months, Yoon was removed from office through the parliamentary impeachment procedurethen confirmed by the Constitutional Court. In January 2025, after attempting to resist arrest by barricading himself in the presidential residence, he was finally detained. He had already been sentenced to five years in a first trial for having obstructed the police and for having drawn up a false document that attributed the approval of martial law to the prime minister and the minister of defense, a document which he then destroyed.

The main trial, which ended on 19 February 2026, saw him answer to the most serious charge: having led an insurrection against the State. The court found him guilty and sentenced him to life imprisonment. Yoon has always maintained that he acted to defend democracy from opposition obstructionism. A defense that the judges did not consider credible.

The role of far-right YouTubers

But how do we get to this point? How can a President of the Republic, a former prosecutor, a man who has studied the law for decades, convince himself that he should send the military against the parliament of his own country? A partial but significant answer comes from the way Yoon had informed himself in recent years. According to reconstructions by the main Korean media, also taken up by international analysts, Yoon had become a regular consumer of far-right YouTube channelswhose influence on Korean politics has grown enormously over the past decade.

In South Korea, YouTube has become the main source of information for a significant portion of the population, replacing traditional media. 54 percent of South Koreans say they get their information on the platform, and for 70 percent of participants at conservative rallies, YouTube is even the primary source of news. In this ecosystem, a galaxy of far-right influencers, some with over a million subscribers, have thrived by spreading conspiracy theories, fake news and incendiary rhetoric.

One of the most emblematic channels is called “The Hand of God”: in the months preceding the martial law it had published videos explicitly asking the president to proclaim it. Another influencer, Ko Sung-kook, owner of the Kosungkook TV channel with over a million followers, had built his fortune on the denunciation of phantom electoral fraud, claims denied by all Korean courts, and on the narrative of a pro-North Korean conspiracy within the institutions.

These channels had focused in particular on the National Election Commission, portraying it as the operational center of a system of fraud in the 2024 parliamentary elections, which Yoon had clearly lost. Well, it’s exactly this conspiracy theory that seems to have convinced the president to order the special forces raid against the Commission. A raid, we remember, which found absolutely nothing.

The JoongAng Ilbo newspaper had described Yoon as “addicted to YouTube”. His own Unification Minister, Kim Yung-ho, had posted over 5,400 videos on the platform before being appointed, many of them containing disinformation about North Korea. Yoon’s government, in other words, had absorbed the worldview of the conspiracy blogosphere and translated it into state policy.

A lesson for everyone

It would be convenient to dismiss this story as a distant story, typical of cultures different from ours. It would be a mistake. The mechanism that led Yoon to believe in YouTuber conspiracy theories is the same one that operates in our families and communities. Disinformation channels work because they leverage real emotions: fear, a sense of injustice, distrust towards institutions. They offer simple explanations to complex problems. They create a sense of belonging, a community of “enlightened ones” who see what others do not see. And gradually, through the algorithm that rewards the most extreme and sensational contents, they lead those who watch them towards increasingly radical positions.

It is not a problem of intelligence or education: Yoon was a lawyer by profession. It is a problem of human vulnerability to the information bubble which always gives us back only what we want to hear, amplified and distorted. We are called to educate ourselves and our children in a critical use of the media, recognizing that no algorithm is neutral and that the ease with which news flows on our screens is not a guarantee of truth.

South Korea was able to react: its parliament resisted that December night. His judiciary has run its course. Democracy held. But the price paid, in terms of instability, fear, lost trust in institutions, was very high. And the poisonous seed of disinformation continues to germinate, in Korea as elsewhere. THEYoon Suk-yeol’s life sentence is justice. But the real question that this story leaves us with isn’t about him: it’s about usand the way we choose to inform ourselves every day.