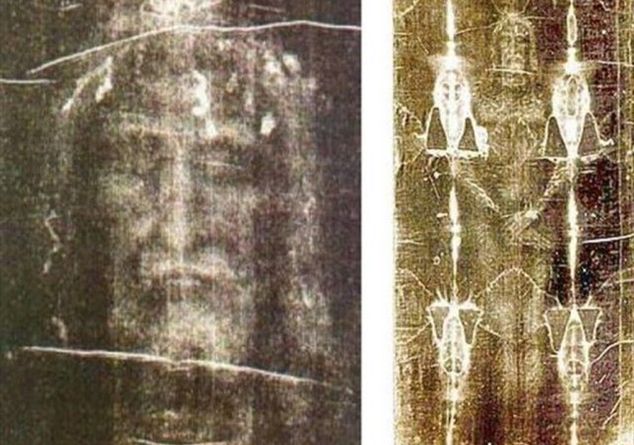

The Shroud is a flap linen sheet. It is 441 centimeters long and 113 wide. Since 1578 it has been kept in Turin. On the towel – light ocher yellow color – footprints are visible that reproduce images (front, left; dorsal, right) of A man who died following a series of torture culminating with crucifixion. There are also two black stringed black lines and a series of white pieces: it is the damage due to the fire in Chambéry in 1532.

According to tradition, it is the sheet mentioned in the Gospels that served to wrap the body of Jesus in the sepulcher. The subject of constant scientific research, represents a direct and immediate reference that helps to understand and meditate on the dramatic reality of the passion of Jesus. On May 24, 1998 Pope San John Paul II called it “mirror of the Gospel”.

On May 2, 2010, during his visit to Turin, Pope Benedict XVI He called it “Holy Saturday icon”. Here is the full text of its meditation:

All the photographs of this service are from the Ansa agency except those that make up the cover, which are from the Reuters agency.

Dear friends,

This is for me a highly anticipated moment. On several other occasions I found myself in front of the Sacred Shroud, but this time I live this pilgrimage and this stop with particular intensity: perhaps because the passing of the years makes me even more sensitive to the message of this extraordinary icon; Perhaps, and I would say above all, because I am here as a successor Di Pietro, and I bring the whole Church in my heart, indeed, all humanity.

I thank God for the gift of this pilgrimage, and also for the opportunity to share a brief meditation with you, who was suggested to me by the subtitle of this solemn ostention: “The mystery of Holy Saturday”. It can be said that the Shroud is the icon of this mystery, the Holy Saturday icon. In fact, it is a sepulchral sheet, which enveloped the body of a crucified man corresponding to what the Gospels tell us of Jesus, who, crucified around noon, pushed around three in the afternoon.

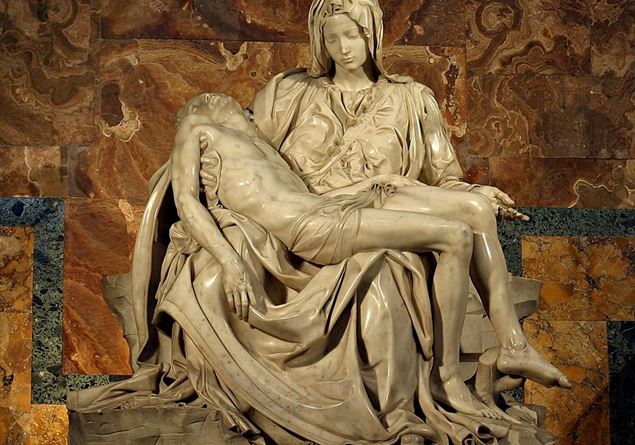

Came in the evening, since it was the parasceve, that is, the eve of the solemn Easter Saturday, Giuseppe d’Arimatea, A rich and authoritative member of the Sanhedrin, courageously asked Pontius Pilate to be able to bury Jesus in his new sepulcher, who had made himself dig into the rock not far from Golgotha. Once the permit was obtained, he bought a sheet and, deposited the body of Jesus from the cross, wrapped him with that sheet and put it in that tomb (cf. Mk 15:42-46).

Thus reports the Gospel of San Marco, and with him the other evangelists agree. From that moment, Jesus remained in the sepulcher until the dawn of the day after Saturday, and the Shroud of Turin offers us the image of as his body was lying in the grave during that time, which was short chronologically (about a day and a half), but was immense, infinite in its value and in its meaning.

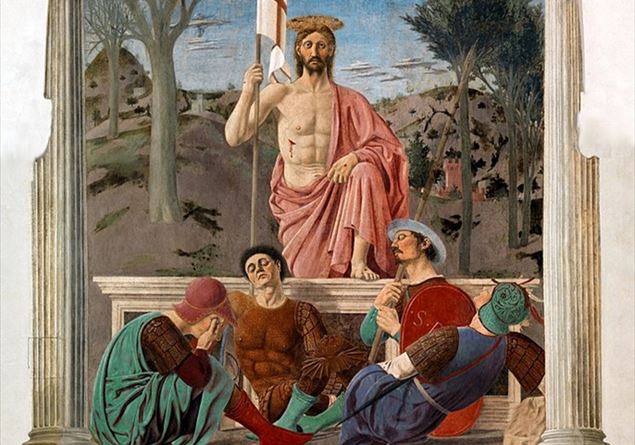

Holy Saturday is the day of God’s hidingas we read in an ancient homily: “What happened? Today on earth there is great silence, great silence and solitude. Great silence because the king sleeps … God died in the flesh and went down to shake the kingdom of the underworld” (Homily on Holy Saturday, PG 43, 439). In the creed, we profess that Jesus Christ “was crucified under Pontius Pilate, he died and was buried, descended to the underworld, and on the third day he raised from death”.

The hiding of God is part of the spirituality of contemporary man

Dear brothers and sisters, in our time, especially after crossing the last century, humanity has become particularly sensitive to the mystery of Holy Saturday. The hiding of God is part of the spirituality of contemporary man, in an existential, almost unconscious way, like a void in the heart that has been widening more and more.

At the end of the nineteenth century, Nietzsche wrote: “God is dead! And we killed him!”. This famous expression, on closer inspection, is taken almost literally by the Christian tradition, often we repeat it in the Via Crucis, perhaps without fully realizing what we say.

After the two world wars, the concentration camps and gulags, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, our era has become more and more a Holy Saturday: the darkness of this day appeals all those who ask themselves about life, in particular we ask us believers.

We too have to do with this darkness. And yet the death of the Son of God, of Jesus of Nazareth has an opposite, totally positive aspect, a source of consolation and hope. And this makes me think of the fact that the Sacred Shroud behaves as a “photographic” document, with a “positive” and a “negative”. And in fact it is just like that: the darkest mystery of faith is at the same time the brightest sign of a hope that has no boundaries.

Holy Saturday is the “nobody’s land” between death and resurrection, but in this “nobody’s land” one entered one, the only one, who crossed her with the signs of her passion for man: “Passio Christi. Passio Hominis”. And the Shroud speaks to us exactly of that moment, it is clear precisely that unique and unrepeatable interval in the history of humanity and the universe, in which God, in Jesus Christ, shared not only our dying, but also our remaining in death. The most radical solidarity.

In that “Oltre-the-time time” Jesus Christ is “descended to the underworld”. What does this expression mean? He means that God, who has made man, has come to the point of entering the extreme and absolute solitude of man, where no love ray arrives, where total abandonment reigns without any word of comfort: “the underworld”.

Jesus Christ, remaining in death, exceeded the door of this last solitude to guide us too to pass it with him. We all sometimes felt a frightening feeling of abandonment, and what death is more afraid of us is just this, as children are afraid of being alone in the dark and only the presence of a person who loves us can reassure us.

Here, this happened on Holy Saturday: the voice of God was resounded in the kingdom of death. The unthinkable happened: that is, love has penetrated “in the underworld”: even in the extreme darkness of the most absolute human solitude we can listen to a voice that calls us And find a hand that takes us and leads us out. The human being lives for the fact that he is loved and can love; And if love has penetrated in the space of death, then life has also arrived there. At the time of extreme solitude we will never be alone: ”Passio Christi. Passio Hominis”.

In the breast to death, life is now pulled, as love uninhabitants.

This is the mystery of Holy Saturday! Just beyond, from the darkness of the death of the Son of God, the light of a new hope has sprung up: the light of the resurrection. And here, it seems to me that looking at this sacred cloth with the eyes of faith you perceive something of this light. In fact, the Shroud was immersed in that deep darkness, but it is at the same time bright; And I think that if thousands and thousands of people come to venerate it – not to mention those who contemplate it through the images – it is because in it they do not see only the darkness, but also the light; Not so much the defeat of life and love, but rather the victory, the victory of life on death, of love on hatred; They see the death of Jesus, but glimpse his resurrection; In the breast to death, life is now pulled, as love uninhabitants.

This is the power of the Shroud: from the face of this “Man of pain”which brings the passion of man of all time and every place on himself, even our passions, our sufferings, our difficulties, our sins – “Passio Christi. Passio Hominis” -, from this face he promises a solemn majesty, a paradoxical lordship. This face, these hands and feet, this cost, all this body speaks, is itself a word that we can listen to in silence. How does the Shroud speak? Talk to blood, and blood is life!

The Shroud is an icon written with blood; Blood of a flagellated man, crowned with thorns, crucified and wounded at the right cost.

The image impressed on the Shroud is that of a dead man, but the blood speaks of his life. Every trace of blood speaks of love and life. Especially that abundant stain close to the cost, made of blood and water that came out copiously by a large wound obtained by a Roman spear blow, that blood and that water speak of life.

It is like a source that murmurs in silence, and we can hear it, we can listen to it, in the silence of Holy Saturday.

Dear friends, we always praise the Lord for his faithful and merciful love. Starting from this holy place, we bring the image of the Shroud into the eyes, we bring this word of love into the heart, and we praise God with a life full of faith, hope and charity. Thank you.