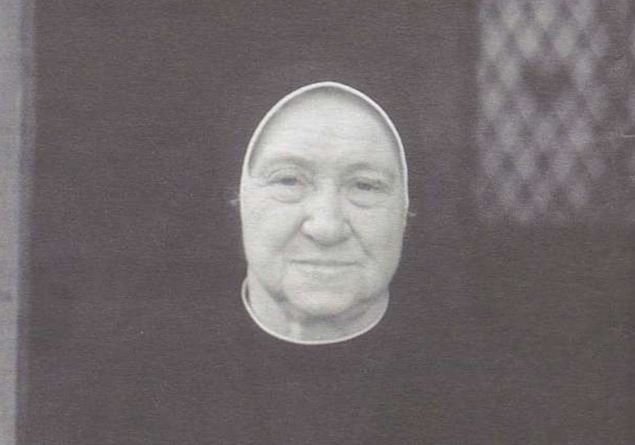

“I was in prison and came to see me.” Gesu ‘leaves no margin to doubt when in the Gospel it indicates the “straight way” that leads to help the people of prisoners, beyond the faults committed. It is a long and complex road, difficult to travel. Among the few to succeed, Sister Gervasia Asioli, Orsolina delle daughters of Maria Immacolata, per century Adele Asioli, born in Desenzano sul Garda on May 19, 1917 and disappeared in Verona on 18 July 2010. A dedicated life, among the penitentiary institutions of Verona and Rome (Rebibbia), in Ergastolani, former terrorists Rossi and Neri, ex -Brigatisti, sentenced for brigat. assassination and for heinous crimes. But also to common prisoners, homosexuals, transsexuals and prostitutes with problems of justice, that is, that people of forgotten pending the “end penalty”, who had a “sincere friend” in Sister Gervasia, a “older sister”, almost “a mother” ready to help them, in application of the evangelical “I was in prison …”. Note and less known names that do not go unnoticed like Francesca Mambro and her husband Valerio “Giusva” Fioravanti, Gilberto Cavallini, Domenico Papalia, Vincenzo Andarus, Dario Mariani, Johnny Lo Zingaro, Alfredo Visconti “Fantomas”, cared for by the religious as “adoptive children”.

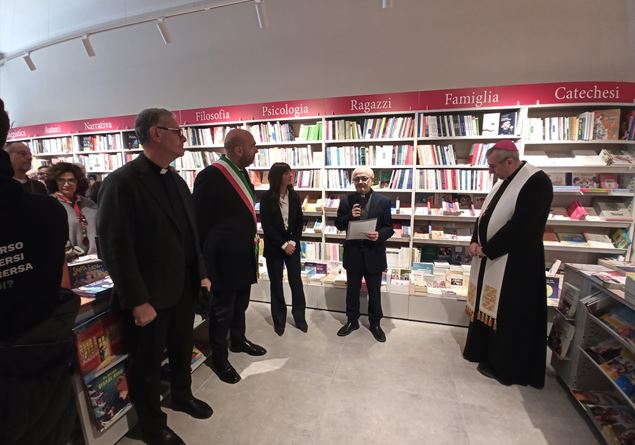

For the first time, Emanuele Roncalli (great -grandson of S. Giovanni XXIII) and Gabriele Moroni speak in the fresh book book “One nun in hell” (Marietti Editore, 140 pages, € 16.50). A biography made even more engaging by the publication of some unpublished letters between the prisoners and the religious defined by Roncalli and died “historical figure of the world of prison who spent his entire life in penitentiary institutions”, free from the rigid canonical constraints in force in convents and monasteries. But also “a countercurrent woman, without prejudices, often uncomfortable”, always ready to defend the human rights of prisoners. “We have 3-seater cells with 9-10 prisoners inside. It is inhuman,” he denounces Sister Gervasia in a letter to the judicial authorities, pushing himself to publicly declare-on the model of Popes such as St. John Paul II and his successors-in favor of the humanization of the penalties and the redemption of prisoners. “I am for the pardon. Other than prison! I met brigatists, scammers, thieves, killers, pedophiles, robbers and I acquit everyone, good and bad. To judge them, Jesus will think about it in the afterlife,” he has in fact written and shouted the religious. Certainly stinging positions for right -thinking and conservatives inside and outside the Church, but which Sister Asioli has always proclaimed without being intimidated. A political-religious identikit confirmed by the deputy Simonetta Matone, long-term magistrate, for years the judge of surveillance of the Court of Rome, who in the preface to the book-entitled, not surprisingly, “A revolutionary nun” – he writes, among other things, that “Sister Gervasia was a mythological figure, for his being a religious outside the box, revolutionary out of any convention … he was politically incorrect, he pursued only one goal: the good of the prisoners”. “He was in no way interested in who they were and what they had done,” Matone underlines, because “he was interested in their present, their conditions behind the bars” and “he believed that prisons were hell and that his goal was to alleviate those penalties …”. However, he still reveals the magistrate now deputy of the League, “she believed the prayer important, but up to a certain point, because then we had to be aware with the being Christian. And her militant Christian being was on the side of the prisoners and with the prisoners …”.

Natural, therefore, that between Sister Gervasia and the prisoners immediately was born a feeling made of trust and mutual affection, in direct interviews and in letters, “in a private, intimate dimension, not without weaknesses and sagging, with continuous references – write Emanuele Roncalli and Gabriele Moroni – to the years of lead, at the darkest periods of the first Republic, stained by attacks, seizures of person, murders “. In these letters, the authors note, “the massacre of Bologna, the crime Piersanti Mattarella, ambushes to mafia bosses, the riots in the prisons, the largest millionaire bluffs, emerge in watermark, recalled, debated by those who do not deny having been ‘saints’, but often deny having been involved in such facts …”. As confida Valerio “Giusva” Fioravanti, sentenced in 1988 with his wife Francesca Mambro for armed gang and for the attack on the Bologna station, in a conditional freedom since 2004 and free since 2009. “I have been tired – Fioravanti writes on June 9, 1988 – the trial approaches at the time of the sentence and in the long run I also refurbished the tension. In many years this is the first time that I have a process as an innocent and I find myself with the emotions and measures And the disappointments and hopes of any prisoner.

The epistolary relationship with Francesca Mambro, who in a letter dated January 28, 1989 complains, among other things, to have never made fun of anyone in a letter and let alone the trust of those who gave me understanding, patience and attention. I have no idea what is happening out and because of this yet another conspiracy on our damages “by those who” are interested in the crystallization of the stereotype ‘monsters’, ‘killer’ Of this or that other … “. Letters – according to Roncalli and Moroni – from the content of sincere friendship that will never come without even after the extinction of the Mambro penalty”, which also confesses that he had “a psychological collapse after the July sentence in Bologna”. These are, the authors point out, “the outcome of the first instance trial on the Bologna massacre ended with the sentence of 11 July 1988, with life imprisonment to her and Valerio Fioravanti, Massimiliano Fachini and Sergio Picciafuoco”. Religious contents, and full of gratitude, also characterize the letters of Gilberto Cavallini, among the founders of the Nar, sentenced for terrorism in the 1980s, and for the assassination of the deputy prosecutor Mario Amato and the massacre of Bologna. “Dear Sister Gervasia – writes on March 26, 1990 – in our meetings and in our chats I saw your ability to dedicate yourself to others and to love all regardless of the political color, the race, the type of rest and so on … I was able to touch the most appreciated feeling of our Lord with your hand, which I try not to disappoint even if obviously I am still very far from being a exemplary follower of Christ …”. Words and feelings present in all the other letters, as a sort of ideal umbilical cord between Sister Gervasia and “his” prisoners, a thread of hope always alive that the “revolutionary” religious will never cease to weave until the end of his time.