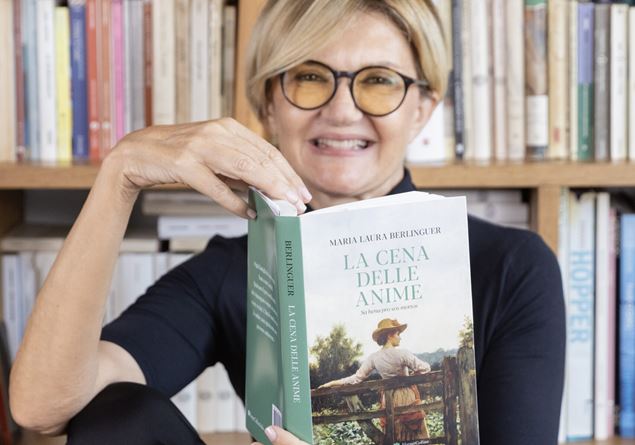

An abandoned house, a removed past, a daughter who returns to mend a bond that death has never really cut. The Soul dinner (Harpercollins), is the debut novel by Maria Laura Berlinguerprofound connoisseur of the most authentic Italian soul. And it is a powerful novel, on the return, on the wounds, on the love that does not go out, on the invisible that unites us, in an harsh and poetic Sardinia where the stones retain the secrets.

What does the ritual of the soul dinner consists of?

“It is an ancient Sardinian custom, still alive in some areas of the interior, especially in Nuorese, where it is believed that the ancestors do not die, but go to a parallel world, and that in some days the border between the two worlds are thin and these souls return to the houses not with bad intentions but as guiding spirits. Thus, in the night between 1 and 2 November the families left the table for the deceased, with their favorite dishes and more precious equipment. It was a way to remember them, honor them, but also to hear them still present, as if they could return for one night. I chose this title because my protagonist does exactly this: he takes a heart table to break the silence handed down among the generations, to give voice to those who have not been able to speak, to confront the ghosts and re -establish family threads, finding herself “.

And what does the dinner of soul dinner represent for you?

«The human heart of history. It is a symbolic gesture that restores dignity to memory and makes death less distant, less cruel. For me it is also an act of love: setting for an absence means recognizing a profound presence, which still accompanies us. It is the link with the family, not seen as nostalgia, but as an identity research of one’s origins, as a female redemption ».

What meaning is attributed to death?

«Death is not the end, but a passage, and this is a universal message. Recovering the voice of our ancestors makes us less alone. It is a death that does not separate, but unites. The book returns a sense of continuity, not of rupture ».

Even when it is painful to know your family history, as in the case of the protagonist?

“Yes, because knowing the past makes us free.”

What prompted her to return to her Sardinian roots? Was it more an intimate need or a narrative urgency?

«It was an almost visceral deep call. I wanted to tell a land I know in the blood before even in geography. There is a real part in this novel, because Vincenzo Dessì was my great -grandfather, an archaeologist, a very caught man of a Sardinia who comes out of his stereotypes. And I wanted to tell a different island. In Sardinia there was an advanced circle and of cultural thickness, refined, which ordered clothes in Turin and Paris and discussed philosophy and archeology. Among the protagonists of that season there was Vincenzo Dessì. His collection today is kept in a dedicated room in the Sanna di Sassari Archaeological Museum, donated by my grandfather. This, for me, represents a concrete bridge between family memory and collective history ».

What kind of family was his?

“My family is of enlightenment traditions, there was not so much space for this type of culture that, however, ancestral Sardinia preserves. These are experiences that initially were not part of my personal story, but that I recovered because I have a secular and pragmatic vision, experiences that made me much stronger. I did an in -depth study on the cultural, anthropological, sociological and spiritual background of Sardinia, and all this has humanly enriched me ».

In the novel, memory is almost a character. How important is the past in your idea of identity?

«It is important to know who we are and where we come from. There is a branch of psychology, transgenerational psychotherapy, or psychogenenalogy, which teaches us that we are also the fruit of collective memory: we bring with us, unconsciously emotional inheritance, trauma, silences and even errors of the generations that preceded us. Sometimes those silences turn into internal crypts. Only by looking at them in the face, exploring them, can we get rid of burdens that each family, to some extent, brings with them. This is not a nostalgic research, but alive, active, necessary. For me it was a way to return light to parts remained in the shadow of my family: to do justice to an archaeologist like my great -grandfather Vincenzo Dessì, now little known, and together redeem the value of female awareness. In the nineteenth century there were women who were not only marginal or backward figures, but travelers, cultured, silent protagonists with cultural and social records that history has not been able to retain. Giving voice to this invisible Sardinia was a profound need, almost an inner duty ».

The theme of female identity and the search for self -determination emerge in the novel. Miriam and Iride seem two specular figures, both on the way to a form of personal and profound freedom. Is that so? Is this what he wanted to tell through them?

«Yes, Mimì and Iride embody two women looking for freedom: one through friendship with Elisabeth and illegal love, the other through comparison with their genealogy and the choice to stay or leave. They are both looking for a space in which to express themselves, of a voice that is not the reflection of the expectations of others, but authentic manifestation of oneself. There is a very strong relationship between Tata and Iris in the present and between Mimì and Elisabeth in the past, and both work to free women through the secrets. I believe a lot in female relationships, I believe in the friendship between women and in the strength of women to overcome problems “.

They are strong but silent women. In Mimì and Iride how much is his experience or his female genealogy?

“Very, very much. We are the characters we write. Everyone draws on their own heritage. There is a lot of the women who surrounded me and I have heard of. Silence in Sardinia is the real unique language. Silence speaks, as Michela Murgia wrote ».

The brigand Emanuele embodies forbidden love, but also rebellion. Is love in the novel more a refuge or a political act?

«Maybe it’s a political act. Not so much in the ideological sense, but because it becomes something for which you fight is rebellion against what oppresses, against the roles imposed. Love in this case is chosen, courage, stance ».

Sardinia you tell is almost mythological. Is it a land that retains, that consoles or that frees?

«It holds out but also free. It does not console: it is harsh ».

In times of artificial intelligence and dematerialization of feelings, she has instead chosen memory, slowness and spirituality, giving voice to women and minor places that contain universal truths. An ethical choice?

«Yes, it was an ethical choice, but before even a personal necessity. In an era dominated by speed and artificial intelligence, I felt the need to slow down, to return to memory, to listening to long time. It is a form of free research, which does not bend to efficiency but to inner truth ».

Between collective mourning and small rites, the novel makes death and rebirth coexist. A powerful message in these post -pandemic years …

“It was the message I wanted to convey. Death is not the end of life, but part of a wider cycle that also includes rebirth. After the experience of Covid, I felt the need to remember him. In this, religion has always played a fundamental role: that of giving meaning, strength and hope even in the darkest moments ».