Italy’s hospital care is improving, but not enough to truly be called “a” national healthcare system. The photograph taken by National outcome program 2025 (PNE), presented by Agenas to the Ministry of Healthin fact, gives a chiaroscuro picture: the overall indicators are growing, the structures that reach high standards of quality and safety of care are increasing, but the territorial gap remains profound. And it continues to run especially along the North-South axis.

The most evident data may seem encouraging: there are 15 “top” hospitals, capable of simultaneously excelling on various clinical, organizational measures and health outcomes. The downside, however, is clear: almost all of these excellences are concentrated in the North, with only one leading structure located in the South. In the South, as often happens in reports on Italian healthcare, the picture is more nuanced: good professionalism and individual points of quality are not lacking, but the ability of regional systems to guarantee homogeneous standards still remains fragile.

The PNE allows the quality of care in Italy to be measured every year through dozens of indicators, ranging from the management of cardiovascular emergencies to the treatment of tumors, from major surgical interventions to assistance for chronic pathologies. The 2025 edition shows an overall positive trend: clinical outcomes improve, complications and adverse events decrease in many cases, the number of facilities able to respect the recommended times for the most urgent treatments increases.

A significant element concerns time-dependent treatments. In cases of heart attack, for example, the number of patients treated within international standards is growing, a sign that emergency networks are working better than in the past. Even for stroke there is a greater diffusion of specialized units and a better ability to intervene in adequate times, with direct benefits on survival and neurological outcomes.

The paradox of fragmentation

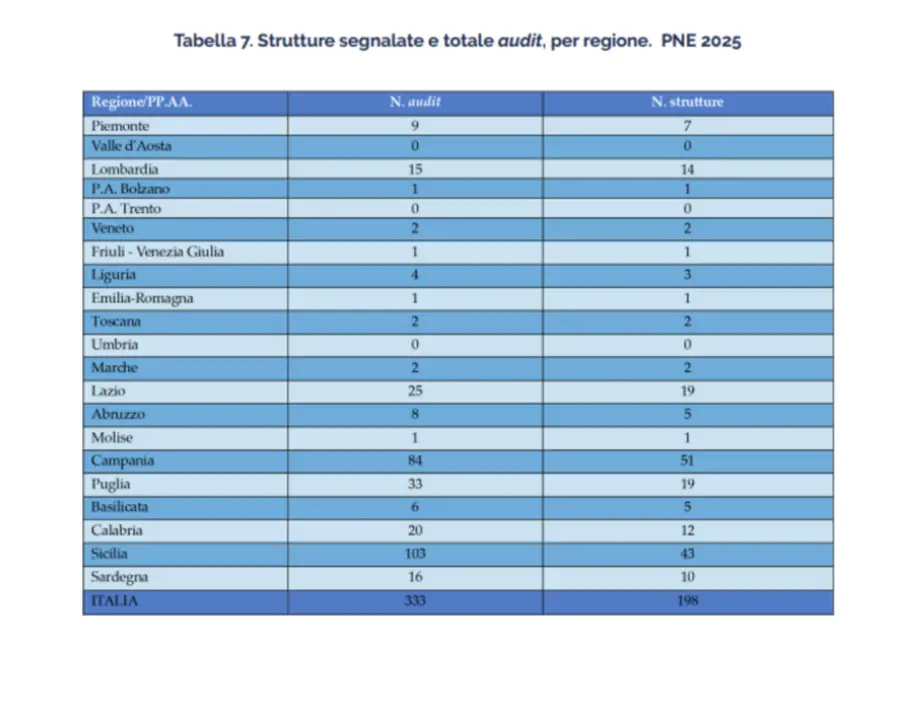

But the average improvement is accompanied by an increasingly evident paradox: the fragmentation of the system. Italy is not a country where the quality of care is low; rather, it is a country where quality is highly unequal. Approximately two out of ten hospitals are still “postponed”, that is, unable to reach acceptable standards on multiple indicators. And the majority of these structures are located in the Centre-South, where organizational criticalities, staff shortages, reduced technological equipment and less integration between hospital and territory are more often combined.

The result is healthcare with variable geometry: being born or falling ill in one region rather than another can concretely change the probability of access to timely and effective care. These are not just perceptions: they are data that emerge forcefully from the report.

The fifteen hospitals of excellence identified by the PNE have become true reference models: structures that manage to combine clinical effectiveness, correct use of resources, patient safety and appropriateness of interventions.

These hospitals have solid interdisciplinary networks, stable organizational processes, effective use of technologies and staff planning consistent with real needs. A mix that produces tangible results: fewer surgical complications, fewer repeated hospitalizations, quicker treatment and survival rates higher than the national average for the most serious pathologies. The problem, however, is not the islands that work, but the difficulty in creating a system: too many good practices remain confined to local realities without managing to become the common heritage of the National Health Service.

The North-South divide

In the South the picture remains more fragile. There is no shortage of excellent departments and top-level professionals, but these often coexist alongside undersized or poorly integrated services. Southern regions struggle to ensure adequate volumes for some complex procedures — a factor directly related to clinical outcomes — and to stabilize medical and nursing staff.

Furthermore, in many areas a hospital-centric organization persists which struggles to communicate with the local area: overloaded emergency rooms, fragmented processes for taking care of chronic conditions, difficulty in guaranteeing continuity of care after discharge. These are structural weaknesses that also fuel the phenomenon of healthcare mobility: tens of thousands of patients move from the South to Northern regions every year for specialist interventions and treatments. A flow that is not just a question of money – we are talking about hundreds of millions of euros that “travel” together with patients – but also of trust: where the perception of quality is not solid, geographical distance weighs less than the hope of obtaining better care.

Personnel and organisation: the main issues

From the Agenas data, the two great challenges still open clearly emerge: personnel and organisation.

In terms of healthcare workers, many facilities, especially in the Center-South, experience a chronic shortage of doctors, nurses and technicians. Competitions are often deserted, turnover slows down, workloads increase. Both the quality of care and the ability to plan stable services over time are affected.

On the organizational side, the difficulty in building truly integrated clinical networks weighs heavily: trauma centers, stroke networks, coordinated oncology, widespread telemedicine are still too unequal. Where these networks work – as in some northern regions – the indicators are rewarding; where they are missing, performances are more uncertain.

The 2025 PNE arrives at a crucial moment: the implementation of the health PNRR, with the creation of community homes and hospitals and with the strengthening of local medicine, could contribute to reducing precisely those differences that weigh the most today. Bringing more prevention, more home care and multidisciplinary care close to people means relieving hospitals of inappropriate performance and concentrating resources where they are really needed: emergencies, complex pathologies, specialist interventions.

But the challenge remains to be played: without a homogeneous regional planning capacity and without stable investments in personnel, the risk is that these reforms will also remain patchy.

A healthcare that is “going”, but not yet for everyone

The Italian healthcare system of 2025 is therefore not a country in disrepair. On the contrary, it is a nation that shows solid peaks of excellence, internationally recognized skills and a continuous average improvement in standards of care. But it is also a system that still fails to guarantee equal health rights to all citizens, regardless of their place of residence.

The PNE’s message is clear: we can do better, because the models that work already exist. The challenge now is to transform those excellences into widespread normality, making quality a shared heritage and not a geographical privilege.

Because the heart of truly public healthcare is not just treating well, but treating well everywhere.