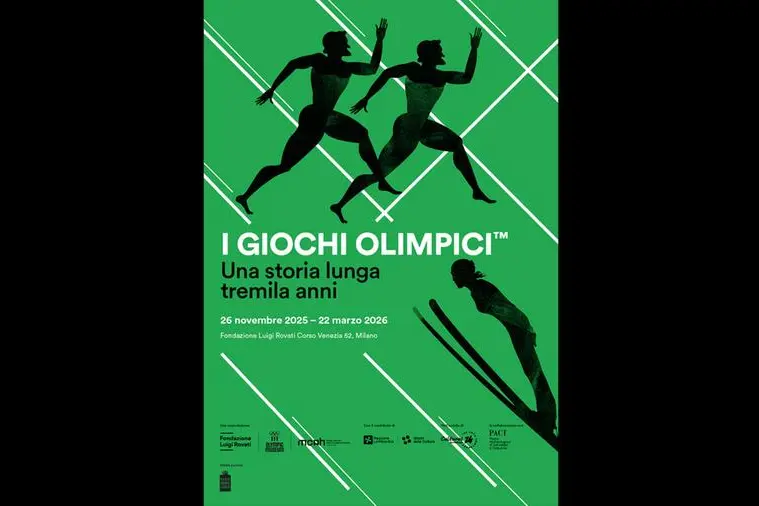

The essence of the Games is there in a history that unfolds over 3 thousand years, from Olympia 776 BC (more or less because historians are wary of the clear date) to today: in the intersection of ancient and modern suggestions, in the competition inherent in the human, in the sacred and profane meanings that have been attributed to it over the millennia. The exhibition The Olympic Games, a three thousand year long history, until March 22nd at the Luigi Rovati Foundation in Milan, makes it plastic.

A project curated by Anne Cécile Jaccard, Patricia Reymond, Giulio Paolucci and Lyon Pernet, created in collaboration with the Olympic Museum and the Musée Cantonal d’Achéologie e d’Histoire, both from Lausanne, and with the important contribution of the collection of the Archaeological Park of Cerveteri and Tarquinia and the Vatican Museums.

Splendid in its hybridity between today and ancient, between archaeological and sporting, between history and stories, with a capital letter and a lowercase letter, the exhibition is set up in the headquarters of the Foundation in Corso Venezia in Milan, with the collaboration of institutions that mix different knowledge in a whole that unites the history of the ancient Olympic Games of the classical world, with the modern ones that started on the inspiration of Pierre De Coubertin in 1896, in a mix of constants, revisitations and changes necessary to resist over time without betraying ourselves and at the same time survive in a world that updates its values.

Now that the competition between Greek city-states with religious implications has become secular and between nations, we are once again talking about an Olympic truce, in the name of neutral and universal Olympism, in a world crossed by winds of great tension, which have not yet been blowing around the Olympic flame. Consider that it has existed as we know it now since Berlin 1936, born to be Hitler’s Olympics and gone down in history as that Jessie Owens, and that even as we write, the flame lit for Milan Cortina a few days ago in Olimpia, is starting its journey in Italy.

On 6 December she leaves for the relay that will take her to light the Milan Cortina tripod at the San Siro stadium on 6 February 2026. The UN resolution on the Olympic truce was approved on 19 November at the United Nations General Assembly with the favorable votes of 160 countries, there were 84 for Paris 2024. As a sign of the commitment of Olympic sport to peace – always distant – in all the Olympic villages of Milan-Cortina 2026, the first widespread Olympics, there will be a symbol: a Wall for the Olympic truce which will give all athletes the space to express their message of peace.

Walking through the exhibition between the main floor and the hypogeum, “underground” called in Greek style in perfect coherence with what you see, the crux of the exhibition connects finds of classical archeology to others of contemporary Olympic history, ancient and modern Games in their materiality, including physical ones: to show the technical, philosophical and cultural evolution.

«The inevitable attention to the sporting event by a large public», writes Giuseppe Sassatelli in the introductory essay of the catalogue, «even if animated by unusual assumptions for a museum, will be an added value of this exhibition proposal, whose cultural message will be able to reach a larger and more diversified number of visitors than the usual users of this type of initiative. An opportunity not to be missed, in line with the Foundation’s mission to reflect on the ancient world in an up-to-date and attractive way.”

Bringing culture and sport out of their respective bubbles is one of the structural elements of the cultural program connected to the Olympic Games in Milan Cortina: «This exhibition, which with the aesthetic charm of the juxtaposition of ancient and modern relics gives the idea of two worlds speaking to each other» he explains, Domenico De Maio, Education & Culture Director of Milano Cortina 2026 «It represents well the basic idea of the cultural Olympicsi.e. the numerous events organized in agreement with the International Olympic Committee approaching and in conjunction with the Olympic and Paralympic Games, whose the objective is to ensure, on the one hand, that culture talks about sport and that the traditional places of culture, from theaters to museums, welcome sporting content, on the other that sport comes out of its bubble and seizes this great opportunity for enrichment in a broad sensecapable of embracing both culture in the strict sense and the great ethical, civil and social potential that sport has within itself and that the values of Olympism represent.”

The synthesis that can be seen in this installation is perfect for achieving the objective of creating osmosis between two audiences that do not always coincide, just as the apparently daring combinations, rather than a caesura, become a bridge in the five sections of the exhibition: it is likely that at first glance archeology speaks to the public passionate about history and culture and that modern relics speak at first to sports enthusiasts, but it is the exhibition itself that guides both to grasp the whole of an interconnected history.

If, on the one hand, amphorae and archaeological finds transmit and render us the aesthetic ideal of the classical athlete who transmigrates from Olympia, preserving his abstractly perfect proportions in the Etruscan worldhistorically in contact with the Greek one, and then in the Roman world; recent symbols show how modern sport has gone beyond that ideal of equal proportions for all, to enhance the differences of bodies which specialize and become, in the diversity of each, functional in the differences to their respective disciplines, including more and more, without losing the essence of competition and the aspiration to victory.

To explain this concept, at a glance, are the small shoes served in the 400 gold hurdles of the very slender Nawal El Moutawakel, the first Arab and African woman to win Olympic gold in Los Angeles 1984; the enormous shoes signed by Michael Jordan, NBA legend and Olympic champion on the parquet in Barcelona 1992, the first edition to admit basketball professionals from North America, and the prosthesis of Urs Kelly, two-time Paralympic long jump champion, used for the gold medal in Athens 2004.

With all due respect to Baron Pierre de Coubertin, inventor of the modern Games, who did not look favorably on professionalism or women, perhaps in retaliation looking down on his boxing gloves displayed on display is the young Boxer painted by Giacomo Gabbiani (1926). Women were already there, despite him, in 1900. They were 2.2%, now they are half. And if it is true that the embryo of the Paralympics would have taken another half century, today we have almost universally acquired that the Paralympic event is definitively a sporting event, not a social one, not of any other nature, guided by the single Olympic motto: citius, altius, fortius to which the “communiter” has recently been added (together) which deserves a separate story.

In a continuous dialogue between modern and ancient, walking through the exhibition one notices, curiously, the fact that “strigils” and containers for ointments in the ancient world were not so dissimilar to the tubes of today’s physiotherapists.

The most evocative and precious element is the transposition of the so-called Tomb of the Olympics, an Etruscan aristocratic tomb (530-520 BC), so called because it was discovered during the preparation of the 1960 Rome Games, and for the sporting subject that the wall paintings represent. Being able to visit it outside the archaeological park of Cerveteri and Tarquinia, recomposed into an exhibition space, which is possible thanks to the fact that the frescoes were removed to ensure their conservation, it is an absolute rarity.

In the end everything converges in the underground section where today’s medals coexist with the Panathenaic amphorae. Filled with oil obtained from the olive groves sacred to Athena and precious in themselves for their decorations depicting the goddess and the competitions of the discipline in question, they constituted the prize for the winners of the Panathenaic Games, while in Olympia the prize was symbolic: an olive crown, sacred to Zeus and imperishable glory.

The same glory that those who win today’s Olympic medals seek, true works of art and design that each Olympic Games designs for itself (those in Turin are on display) through which each athlete seeks the perennial glory linked to the most prestigious title in sport, even now that many will learn only in these rooms that the Nike (Greek pronunciation Nike), literally victory, was a winged woman for millennia before being outclassed by marketing although hopefully, not dismissed, with a mustache on the fabric.