After the raids on Caracas last night, on Saturday morning the president of the United States Donald Trump confirmed the attack on Venezuela and said US special forces had “captured and taken them out of the country” Maduro and his wife Cilia Adela Flores de Maduro. Actual capture? “Negotiated” capture? We don’t know yet.

The events of these hours, still confused and fragmentary, turn the spotlight back on a figure who has governed the Venezuela through repression, international isolation and a progressive suffocation of every critical voice, including that of the Catholic Church.

When Maduro took over the leadership of the country in 2013, he was indicated as successor by Hugo Chavez shortly before his death, he inherits not only the presidency but an entire symbolic and ideological system: Chavismo. More than ten years later, his name is inextricably linked to one of the most serious political, economic and humanitarian crises in Latin America contemporary and to an increasingly open clash with the Church, one of the few remaining institutions capable of denouncing injustices and defending the poorest.

From the suburbs to power

Born in Caracas on November 23, 1962, in a family of modest origins, Maduro grew up in the working-class neighborhoods of the capital. He does not follow a traditional university path: he works as a public transport driver and received his political education in the trade union struggles of the 1980s. It is in this context that a left-wing ideological vision matures, strongly marked by workerist and anti-imperialist rhetoric.

The meeting with Hugo Chávez in the nineties marked the decisive turning point. Maduro joins the Bolivarian project and becomes one of the most faithful collaborators of the future president. His political career progresses rapidly: deputy, president of the National Assembly, then Foreign Minister from 2006 to 2013. Personal loyalty to Chávez, rather than his own charisma, is the main political capital that leads him to the presidency.

Supporters of President Nicolas Maduro and his predecessor Hugo Chavez on the square in Caracas after US raids

(REUTERS)

Post-Chávez: authoritarianism and isolation

Elected in 2013 by a narrow margin and amid strong protests, Maduro finds himself governing a country that is already fragile but still supported by high oil prices. Within a few years, however, Venezuela plunged into an unprecedented economic crisis: hyperinflation, collapse of essential services, widespread poverty and an exodus of millions of citizens.

On the political level, power is progressively concentrated in the hands of the executive. The 2018 elections, judged to lack democratic guarantees by much of the international community, mark a definitive break with the United States and the European Union. Maduro consolidates control over institutions, represses the opposition and drastically limits freedom of the press and expression.

The clash with the Catholic Church

In Maduro’s Venezuela, the Catholic Church is progressively becoming one of the main voices of moral and social opposition to the regime. In the absence of credible democratic institutions and a free press, it is often bishops, parish priests and ecclesial bodies who tell the reality of hunger, forced migration, the collapse of the healthcare system and political repression.

The Venezuelan Episcopal Conference has repeatedly denounced the failure of the Chavista project and the direct responsibility of the government in the country’s crisis, speaking of a “which oppresses the people and denies human dignity”. Statements that provoked violent reactions from those in power. Maduro has publicly accused the bishops of being “enemies of the homeland” and tools of the political opposition and the United States.

It has consolidated over the years a real creeping persecution: priests threatened or attacked during homilies, celebrations interrupted by security forces, defamation campaigns against bishops and lay people involved in social work, bureaucratic obstacles and controls against the Church’s charitable works, especially those that distribute food and medicines in the poorest areas. Particularly targeted were those pastors who took on a prophetic tonerecalling the Gospel and the social doctrine of the Church against the structural injustice of the regime. On several occasions, government officials have openly invited the faithful to distrust their bishops, attempting to break the bond of trust between the people and the Church.

Attempts at mediation were also exploited. The Holy See, involved several times to encourage national dialogue, has clashed with the government’s lack of real will to open democratic spaces. First Pope Francis and then Pope Leo have repeatedly expressed pain and concern for Venezuela, denouncing the suffering of the people and calling for respect for fundamental human rights, but their words have remained largely unheard.

Geopolitics and repression

On the international level, Maduro strengthens alliances with Russia, China, Iran and Cuba, placing Venezuela on an axis openly opposed to the West. The United States accuses him of drug trafficking, corruption and of having transformed the state into a repressive apparatus. Economic sanctions aggravate an already dramatic situation, especially affecting the civilian population.

Power without consent

Especially in recent years, Nicolas Maduro has governed an exhausted country, maintaining power more through the repressive apparatus and the control of resources than thanks to real popular consensus even if the agency Associated Press published a couple of photographs from Caracas in which you can see some people (for now quite a few) holding placards with photos of Maduro.

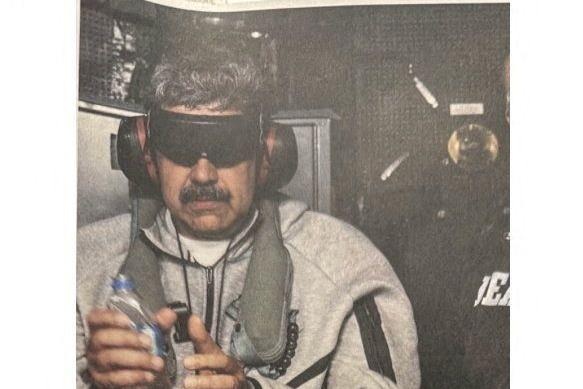

In the months before being captured by the United States, the Venezuelan president had adopted a pacifist rhetoric that was unusual and somewhat clumsy for him. On the one hand it served to present Venezuela as the victim of US encirclement, on the other to try to avoid it. Maduro had begun to address American public opinion in English, even coining a kind of slogan: “No war, Yes peace” (“No to war, yes to peace”). He had it written on red hats, like Trump’s, and he even made a song out of it. In recent days, Maduro had also said he was willing to negotiate with the United States to combat drug trafficking, the pretext for the US pressure campaign and attacks against the boats of suspected drug traffickers.

The portrait of Maduro is that of a leader who, born from the myth of the people, ended up governing against his own people, also entering a collision course with the Church, guilty – in his eyes – of remembering that power can never be separated from truth and justice.