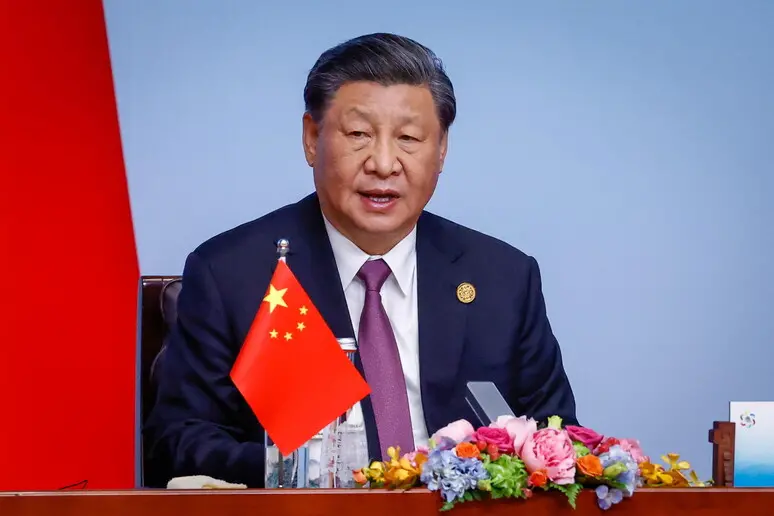

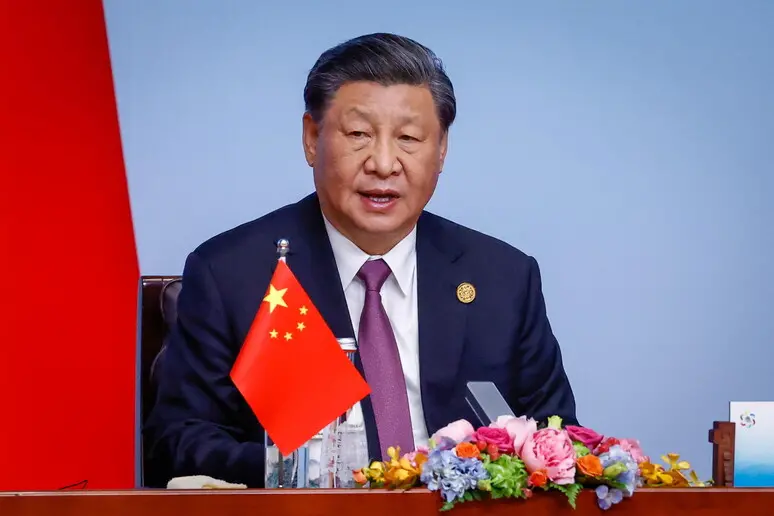

The recent wave of purges that hit the Chinese People’s Liberation Army represents one of the most significant events of the Xi Jinping era. In just two years, the Chinese president has removed dozens of generals, emptying the country’s military leadership. The last blow fell at the end of January 2026, when Zhang Youxia, the highest-ranking general after Xi himself and his childhood friend, was placed under investigation.

The scale of this operation is unprecedented in China’s recent history. The Central Military Commission, the army’s governing body that originally had seven members, is now reduced to just two: Xi Jinping and General Zhang Shengmin, appointed in October 2025. According to an analysis by the New York Times, of the thirty generals who led the army’s most important commands at the beginning of 2023, only five are still in office. Many were replaced, but their replacements were also later eliminated.

A disturbing parallel with Stalin

Chinese Communist Party propaganda justified these purges as necessary to strengthen the military. The official newspaper of the armed forces wrote that there will be pain and difficulties in the short term, but that this will serve to make the army better. The People’s Daily used a metaphor typical of the Maoist era, stating that it is necessary to remove rotten flesh to generate new one.

However, there is a disturbing historical precedent for operations of this type. Between 1937 and 1938, during the so-called Great Terror, Joseph Stalin eliminated approximately ninety percent of the Soviet Union’s military leadership, using similar justifications: it was necessary to eliminate generals who were not loyal enough to the cause to keep the ideological purity of the Party and the armed forces intact, and to ensure complete loyalty towards the leader.

This reference to Stalin’s purges can only arouse deep concern. There dictatorial driftwhen personal loyalty to the leader is placed above competence and service to the common good, has always produced tragic consequences for peoples throughout history.

Taiwan 2027: a deadline that is receding?

According to American intelligence, Xi Jinping allegedly gave his generals a secret objective: by 2027, the year of the hundredth anniversary of the founding of the People’s Liberation Army, the Chinese armed forces should be ready to invade Taiwanthe island that China claims as its own but which is governed in a democratic and de facto independent manner.

This would not necessarily mean that an invasion is imminent or planned, but that the army should have the capabilities to carry it out successfully should the political leader so decide. 2027 also represents the year of the twenty-first Communist Party Congress, when Xi will likely seek to secure an unprecedented fourth term as leader of the Party, government and military.

Now, however, the generals to whom Xi had entrusted these orders have practically all been purged. In the short term, many experts agree that the Chinese military may be weakened and the goal of conquering Taiwan has receded. One of the reasons is that most of the purged generals belonged to operational divisions, and therefore were responsible for the concrete management of military operations.

As he told the New York Times Kou Chien-wen, a professor of political science at Taipei University, said the purges have temporarily reduced the risk of the Chinese Communist Party launching a full-scale war. For Taiwan, this could be a breathing window, albeit a fragile and temporary one.

The danger of absolute power: no one can say no to Xi anymore

However, in the medium and long term, the purges could make the army more efficient, if Xi is able to select new capable generals. But it is precisely here that the greatest risk emerges: the old generals were considered authoritative and powerful enough to stand up to Xi Jinping and counter his possible imprudent decisions.

Zhang Youxia, for example, was a childhood friend of Xi’s. Their fathers had fought together during the civil war that brought Mao to power in 1949. This guaranteed him a certain degree of autonomy from Xi and the ability to stand up to him, discuss his decisions and propose alternatives. Zhang, moreover, had fought in the war between China and Vietnam in 1979: although he was not a moderate, he was an officer who was well aware of the horrors of military conflicts. As Ryan Hass, an expert at the Brookings Institution, observed, eliminating a long-time friend shows that there is no longer any safe zone in China’s power apparatus. The message is clear: no one can feel safe from Xi’s purges.

Now that all the old generals have been purged, Xi could select the army’s new ruling class based not on ability but on loyalty and ideological conformity. Even if he chose the most capable officers, everyone would owe their place to him. This would allow him to gain absolute control of the armed forces. But it would also mean that Xi no longer has anyone capable of standing up to him, anyone capable of telling him if his military decisions are wrong. Shanshan Mei, an expert on Chinese military policy at the RAND Corporation, expressed concern about the lack of real military operational experience at the top. The only remaining vice-president on the Central Military Commission is a career political officer who lacks the operational experience necessary to advise Xi. Who will advise the Chinese president in critical moments? Who will be able to provide him with expert advice when he has to make decisions that could involve the use of military force?

Corruption or political control?

Chinese authorities justified the purges by talking about corruption and the sale of military secrets. Zhang Youxia has been accused of fueling serious corruption problems that threaten the Party’s absolute leadership over the armed forces. Some sources have even spoken of accusations of selling nuclear secrets, an accusation that many experts consider excessive and probably instrumental. It is true that China’s military has been plagued by corruption problemswith generals accused of selling promotions and embezzling funds intended for armaments. But it is equally true that anti-corruption campaigns in China have historically been used as a tool to eliminate political rivals and consolidate the leader’s personal power.

Since 2012, when Xi came to power, more than hundreds of thousands of officials have been investigated or punished. The campaign began with the ousting of Bo Xilai in 2012 and continued with Zhou Yongkang in 2014. It has now reached the highest levels of the military. According to former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, an expert on China, the number of government officials purged under Xi numbered in the hundreds of thousands.

A weaker army now, but perhaps more dangerous tomorrow

Analysts agree that in the short term the Chinese military will be weakened. The purges have hollowed out the chain of command and created uncertainty over who is actually responsible for the day-to-day operations of the People’s Liberation Army. Troop morale could be hit by the realization that not even the most senior and respected generals are safe.

However, if Xi can rebuild the military leadership with competent and fully loyal officers, the military could emerge stronger and more aligned with the supreme leader’s will. This scenario presents significant risks to regional and global peace. An increasingly isolated leader, surrounded only by yes-men without the experience and authority to disagree, could make rash decisions without anyone being able to stop him. It is a dangerous dynamic that history has already shown in other autocratic contexts. Christopher Johnson, a former CIA analyst for China who now heads the China Strategies Group, warned that it would be a mistake for American politicians to see the purges as an opportunity to put pressure on Xi. During the trade escalation with the United States in 2025, Xi repeatedly demonstrated that he was willing to confront Trump even when the outcome was uncertain and his position seemed fragile. Chaos in the military high command limits Xi’s options less than some outside observers might think.

As the history of the twentieth century has taught us, when a leader places himself above all control, when he systematically eliminates anyone who might disagree or offer an alternative opinion, when personal loyalty replaces competence and service to the common good, the doors are opened to enormous tragedies.

China’s military purges are not just a matter of geopolitical strategy or regional balances of power. They are also a deeply human issue that concerns the fate of millions of people living under an increasingly oppressive regime, and the fate of millions more who may be caught up in conflicts triggered by decisions made in the absence of any democratic counterweight. As 2027 approaches, the world watches with growing apprehension the evolving situation in China and around Taiwan. Xi Jinping’s military purges represent a further step towards the consolidation of an increasingly personal and unchallenged power. In the short term, this could delay any aggressive actions against Taiwan. But in the long run, an isolated leader, surrounded only by people who owe him everything and who dare not contradict him, could pose an even greater danger.

Peace is always possible, but it requires wisdom, humility, and the recognition that no human being should ever concentrate absolute, uncontrolled power in his or her hands. It is a lesson that history has taught us at great cost, and one that we cannot afford to forget.