“They become obsessed with numbers rather than how they really feel,” warns Dr. Guy Leschziner, neurologist.

Every morning, as soon as their eyes open, millions of people check their wrist to find out if they slept “well”. This quest for the perfect night hides a little-known side of the coin and ultimately turns out to be harmful to our rest. By transforming sleep into a performance to be accomplished, we create a psychological barrier to falling asleep. The mechanism is simple but formidable: the more you want to “succeed” in your night, the less you succeed. By setting goals for numbers and graphs, the brain unconsciously goes into alert. Instead of indulging in the letting go necessary for sleep, the mind actively monitors whether the body falls asleep well, which maintains a level of alertness incompatible with a peaceful night.

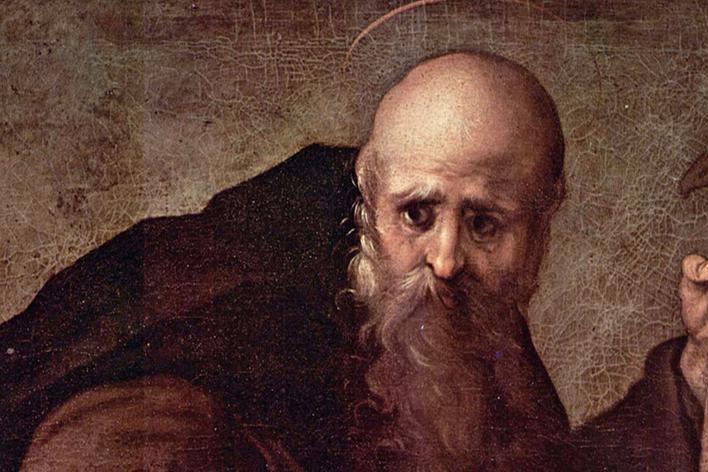

The long-term consequences of this hypervigilance are worrying. By scrutinizing their statistics, the user can slip into chronic anxiety which ends up permanently disrupting their biological clock. “We see many people who have developed severe insomnia as a result of constantly tracking their sleep. They become obsessed with numbers rather than how they actually feelt”, warns Dr Guy Leschziner, neurologist in London in his book “The Nocturnal Brain”. This disconnection between numerical data and physical sensation plunges sleepers into a vicious circle where technology dictates their state of fatigue.

And that’s the whole problem with connected watches. Today, it is estimated that around 30% of adults in developed countries use a device, most often a watch, to track their sleep. This phenomenon has a medical name: orthosomnia. This concept was put forward in 2017 by Kelly Glazer Baron and Sabra Abbott, researchers at Rush University in Chicago, and refers to this obsessive, and paradoxically pathological, quest for sleep optimized by technology.

This psychological pressure is accompanied by a particularly pernicious “nocebo” effect (the opposite of the placebo effect). If your watch tells you when you wake up that you have a low number of hours of sleep (too little deep sleep, or on the contrary too much light sleep) or that your recovery score is low, your brain may begin to produce symptoms of fatigue through pure autosuggestion, even if you initially feel well and rested.

Faced with this trend, French doctors are also starting to warn against this permanent “self-diagnosis”. Dr Marc Rey, President of the National Institute of Sleep and Vigilance (INSV), often reminds us that the best indicator remains the feeling when you wake up and not the numerical data from the application. “The watch can tell that you had 1 hour of deep sleep while you feel good. It’s the feeling that takes precedence, because the algorithms of watches are often opaque and not medically certified“.