To those who remind him that Minister Nordio advised Schlein to vote yes to the reform, “because when you are in Government it will be convenient for you too”, he replies: «I would invite the majority to vote no because when they are at the apposition it will be a guarantee for them too to have an autonomous judiciary independent of the government and parliament».

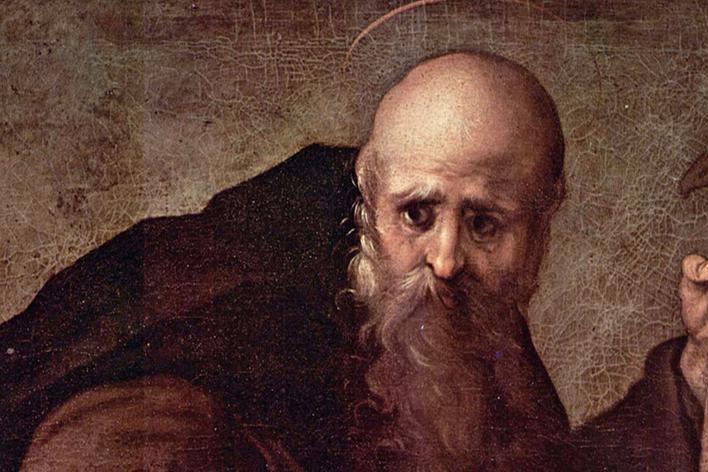

He has a heavy surname, Giovanni Bachelet, president of the Committee for the Yes wanted by civil society. His father, Vittorio, killed by the Red Brigades on 12 February 1980, was vice-president of the Superior Council of the Judiciary. Of that CSM that the Nordio reform would like to “unpack”.

Is this a battle for yes that you are also waging in the name of your father?

«It’s one of the few cases where I have no doubts about what he would think. On many other things the world has changed enormously since 50 years ago, and I wouldn’t be sure what my father would think. On the CSM, however, I am quite certain that it would not be considered prudent to alter the balance of power envisaged by the Constituents. When my father was elected, very young magistrates were also elected from the non-official component, such as Mario Almerighi, one of the “assault magistrates” who had revealed the first big oil bribe. To him, pluralism and the then brand new proportional method of election of the “officers” seemed like an asset: “I would like to underline that this Council, Mr President, begins a new life not only due to the fact that it is renewed due to having held new elections; but also because it is a Council elected on the basis of a new electoral law, which has favored a more varied presence of positions and intentions to guarantee in it a broad representation of all the orientations, forces and contributions present in the Judiciary” (Vittorio Bachelet, inauguration speech as Vice President of the CSM, 21 December 1976). With the draw foreseen by the reform, would we still have an Almerighi in the CSM?”.

Why vote no, then?

«To preserve precious autonomy and independence».

But in the Constitution it will continue to say that the judiciary is autonomous. Isn’t that a guarantee?

«Even in the Constitution of countries such as Russia, Iran and Cuba it is written that the judiciary is independent and autonomous. It is not enough to proclaim, it is also necessary to translate that principle into structural guarantees. In the Constituent Assembly the speaker, when introducing article 105, said that the four powers that the CSM has (i.e. appointments, promotions, transfers and self-discipline) fix the autonomy and independence of the judiciary like four nails, protecting it from the interference of any future minister of Justice. Unfortunately none of the three new bodies (the double CSM, one for prosecutors and the other for judges, and the High Disciplinary Court) no longer has all four of these nails. Not only that: the body responsible for self-regulation – the High Court – is regulated in such a way as to delegate the composition of the judging panels to ordinary law. In other words, while the old CSM had a self-discipline in which the majority of magistrates was guaranteed compared to the representatives of politicians, in the new one an ordinary law will be able to easily establish that the judging panels are made up of two politicians and a magistrate, with a clear change in balance”.

And what about the separation of careers?

«The separation of careers already exists as a result of a series of reforms, the latest being Cartabia. In the five years after the approval of that law less than one percent of magistrates moved from one position to another. Furthermore, even in countries like Portugal, where the separation is complete and there are two distinct CSMs, each retains the powers of our current Superior Council, that is, I repeat: appointments, transfers, promotions and self-discipline. Furthermore, both are elective with a majority of magistrates and a minority elected by Parliament. What in the reform upsets the previous constitutional balance between judicial order and political power has nothing to do with the separation of careers.”

So the problem isn’t the separation of careers?

«For at least 5 years now, the separation of careers between prosecutors and judges has existed in practice, at 99%; but above all, to bring it to 100%, an ordinary law would be enough, discussed in other legislatures and always set aside. What requires a constitutional change is not separation, but rather the abolition of elections for magistrates (in the reform the professional component of the two CSMs is drawn by lot and no longer elected) and the removal of self-disciplinary power from the two new CSMs, entrusted to a third body (who knows why the same for prosecutors and judges; who knows why regulated in many sensitive parts by a subsequent ordinary law). It is a choice of disarticulation and weakening of the judiciary in the face of other powers.”

Those who support the reform say that with the draw the currents will finally be eliminated. Shall we explain to “Mrs. Maria”, to non-technical people, why it is harmful?

«Mrs. Maria should be told that there is also a Facebook group called “abolition of universal suffrage”. That is, there are currents of authoritarian thought that are against free elections. Are the currents in the ranks of doctors or journalists or lawyers or magistrates, or the parties themselves in Parliament a damnation and should be abolished? From the Everyman to the Five Star movement, passing through Almirante, the draw is periodically re-proposed as an antidote to the degenerations of democracy. But I remain fond of the democratic method, the transparency of the mandate, the lists, the free and secret vote.”

Why doesn’t the draw solve the problems?

«I come from the university world and have experience of competitions. When the election is replaced, as has been done, with the drawing of commissions, these become more uncontrollable. With the election there is a transparent mandate and the work of a competition commissioner can be evaluated, for example, on the basis of who voted for him. If instead you draw lots, any opaque operations become easier. Those who have decision-making power are not accountable to anyone and it is not known with what mandate they were elected. Since, however, original sin cannot be abolished by law, if there is, as there is in all decision-making bodies, the temptation to make use of power by choosing one’s friends rather than the best, this temptation will be facilitated, not prevented by this new procedure.”

Nordio himself said that this reform does not serve to make justice more efficient. So what is it for?

«It suggests that the aim is precisely what is denied by the promoters of the yes vote, and that is to shift the balance: a little more power, freer hands for politics (executive and legislative power), a little less power, less autonomy, less independence for the magistrates».

With what effects?

«For example: with a disciplinary court that can be controlled by the Government and the pro tempore majority, would there be the same coverage for the magistrates who carried out the investigations into the mafia massacres, who made it possible to discover the P2 lodge, who conducted the investigations into corruption? If there is no CSM like the one today behind the magistrates, if the magistrates are subjected to disciplinary slap at the pleasure of the politicians, would it be equally easy for them to challenge the established powers to apply the law? And would the magistrates who, with their referrals to the Constitutional Court, triggered sentences that forced politicians to legislate on health, work, education and rights, still do so, under the disciplinary blackmail of those same politicians?

Let’s go back to the separation of careers. It is said that in this way the judge will really be third.

«Of all indictments, a little less than 60% end in a conviction while over 40% end in an acquittal. To me this says that compared to prosecutors, judges are truly third parties, otherwise we would have 100 percent of convictions.”

So are prosecutors the ones who should be more cautious?

«The opinion that the prosecutor should send for trial only when he is certain of the conviction would mean that the only ones sent to trial would be immigrants, drug addicts, street violence and the poor, because only in that case could one be sure that, in the absence of good lawyers and powerful protections, they would be convicted. A great dynamic between prosecution and defense in the trial part and acquittal after different degrees of judgment seems to me to be a sign of the health of justice. The fact that there are many indictments and many wiretaps is linked not to the separation, but to the asymmetry in the initial phase of the investigations. In the initial phase the public prosecutor has more information than anyone and the legislator could and will be able to address this asymmetry, but not through the separation of careers, which has nothing to do with it; if anything, reforming the rules of preliminary investigations”.

The majority says that this referendum must not be a referendum on the government’s approval; does it instead risk being a referendum on the approval of the judiciary?

«Given how this reform was posed and imposed by the government, the related referendum risks being an ordeal. It doesn’t seem good to me either for the government or for the judiciary. Sowing distrust towards the work of the judiciary is very dangerous for the maintenance of a democratic society. On the other hand, a Government that does not even allow an amendment and does not even agree on the date of the referendum vote with the opposition positions itself as the undisputed protagonist of this reform. But we must resist this short-term temptation. This reform does not mainly concern the government, the next elections or the prerogatives of the magistrates. The question concerns us citizens and the constitutional balance of the next 50 years. Do we want the law to remain the same for everyone, including our children and grandchildren? Do we want to give up an autonomous and independent judiciary?”.

The ACLI and part of the Catholic world are also on the no-ai committee. On the other side there is a committee of Catholics for yes. How do you see this different position?

It is not the first time that associations such as the Acli (or Don Ciotti’s Libera, also the founder of our committee together with other large civil society associations) have taken a direct position in political battles or referendums; they, however, do not do so in the name and on behalf of the Church, but under their own responsibility as Christians engaged in the world (as happens to trade unions, parties, movements and individual Christian politicians). I understand that even my Catholic friends who vote “yes”, starting with Stefano Ceccanti, have long been engaged in this battle together with other men and women of good will, without religious labels. From my parents’ stories about the referendum between monarchy and republic in 1946 to my memories of the referendum on divorce in 1974, it appears that in every Catholic family there has always been (perhaps in unequal parts) someone from here and someone from there. So with curiosity I learn of the existence of a committee of “Catholics for yes”, and with relief I can rule out the possibility that a similar committee of “Catholics for no” also exists”.